Right to Work

"Right to work" (RTW) policies undermine unions by preventing them from negotiating contract provisions that require all workers, including non-members, to contribute to the costs of worker representation on the job. "Right to work" encourages workers to "free ride," gaining all the advantages of the union contract without paying a share of the costs of collective bargaining and worker representation. "Right to work" laws do not create a right to employment, do nothing to improve in any way a person's odds of getting or keeping a job, and do not create any jobs.

Major corporate lobbying groups such as the National Right to Work Committee, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and its local affiliates like Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, and the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and its local offshoot the American City County Exchange (ACCE), have been pushing such policies in the United States for decades.[1][2]

Advocates of "right to work" like the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation and the Koch-founded and -funded Americans for Prosperity sometimes claim that the laws are needed to protect workers from being forced to join a union or to pay for political campaigning.[3][4] However, federal law already includes provisions for workers who object to union membership, but who are working as part of a bargaining unit represented by a union, as explained by the National Labor Relations Board: "Even under a security agreement, employees who object to full union membership may continue as 'core' members and pay only that share of dues used directly for representation, such as collective bargaining and contract administration. Known as objectors, they are no longer full members but are still protected by the union contract."[5][6][7]

So-called "right to work" laws do not create a right to have or hold a job, and should not be confused with the "right to work" as described in the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights.[8]

Contents

Koch-Fueled Playbook on Right to Work

The Koch-backed alliance of the American Legislative Exchange Council, the State Policy Network, and Americans for Prosperity follows a predictable script when pushing RTW and other anti-union legislation in the states, as exposed by the Center for Media and Democracy, which tracked the strategy in Michigan, Wisconsin, and West Virginia:

- "a state legislator introduces an ALEC-style Right to Work bill;

- "some think tank experts from SPN or its allies provide "reports" and/or testimony extolling the purported benefits of RTW;

- "and the Koch Brothers' advocacy group, AFP, throws some rallies in while making targeted media buys."[9]

To learn more about the Koch Right to Work playbook, read the Reporters' Guide and related article.

ALEC and Right to Work

| About ALEC |

|---|

ALEC is a corporate bill mill. It is not just a lobby or a front group; it is much more powerful than that. Through ALEC, corporations hand state legislators their wishlists to benefit their bottom line. Corporations fund almost all of ALEC's operations. They pay for a seat on ALEC task forces where corporate lobbyists and special interest reps vote with elected officials to approve “model” bills. Learn more at the Center for Media and Democracy's ALECexposed.org, and check out breaking news on our ExposedbyCMD.org site.

|

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) has promoted a "model" "Right-to-Work Act" since at least 1995.[1] The bill is a product of ALEC's Commerce, Insurance, and Economic Development Task Force, whose members have included representatives of the International Franchise Association and YUM! Brands, as well as McDonald's before the company ended its membership in ALEC in 2012. (See ALEC Task Forces for more information about task force members.) In numerous states, the politicians pushing for right-to-work legislation were members of ALEC, including Michigan,[10] Pennsylvania[11] and Wisconsin.[12]

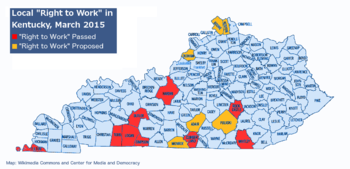

ALEC's local offshoot, the American City County Exchange (ACCE), promotes a local version of right-to-work. As of February 2015, one of the two ACCE "model policies" listed on ALEC's website[13] was a "Local Right to Work Ordinance."[14] ACCE's first meeting also included a presentation titled "Local Right to Work: Protect my Paycheck." ACCE representatives were featured on a Heritage Foundation panel on local right-to-work in 2014, where they spoke alongside Grover Norquist's Americans for Tax Reform and the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation and "highlighted what they viewed as opportunities for local ordinances in Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania."[15]

National Campaign for Local Right to Work

In recent years, major business lobbying groups have begun a campaign for local "right to work" ordinances, which The New York Times has called "a new front in [conservative groups'] effort to reshape American law."[16] The Washington Examiner noted in 2014 that the strategy "may not be legal and has been tried only a handful of times in the last 70 years, and that "[t]he common understanding is that federal law allows only states to enact the measures."[17] Nonetheless, in August 2014 the Heritage Foundation issued a report making the case for local right to work laws,[18] and hosted a panel discussion on the issue featuring representatives of ACCE, Grover Norquist's Americans for Tax Reform, and the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation.[19] The December 2014 ACCE meeting in Washington, D.C. featured a workshop on local right to work, according to the New York Times, which reported that supporters of the effort would first try to pass the legislation in Kentucky, and then try their luck in Republican-controlled states that don't have a statewide right to work law, naming Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin as targets.[20] (Wisconsin passed a statewide "right to work" law a few months later in March 2015.)[21]

In a Dec. 23, 2014 blog post that has since been removed, Stan Greer, newsletter editor for the National Right to Work Committee, suggested NRTWC was no longer backing the local ordinances. "Unfortunately, there is zero reason to believe that any local Right to Work ordinances adopted in Kentucky or any other state will be upheld in court," he wrote.[22]

Business Lobbies Roll Out Local Right to Work in Kentucky

Noting that the strategy is likely to lead to lawsuits, The New York Times reported how a "carefully devised plan" rolled out in Kentucky beginning in December 2014, with several counties passing right to work ordinances within a matter of weeks. The coalition pushing for local right to work in Kentucky includes ALEC, Heritage, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and the Bluegrass Institute, among others.[16]

In February 2015, the Courier-Journal reported that with six county ordinances passed and six more proposed, "Kentucky is at the forefront of a national effort to pass local laws in the 26 states that haven't approved such statewide legislation -- an effort that has already drawn a federal lawsuit challenging the right of counties to do that."[23] The lawsuit was filed by nine labor unions in January 2015, and as of February 2015 had not yet been resolved.[24]

The Daily Caller reported in July 2015 that Americans for Prosperity planned to contribute $50,000 to Protect My Paycheck, an organization involved with the effort in Kentucky.

- "Americans for Prosperity has been instrumental in connecting Kentuckians to policymakers on the need for worker freedom," Brent Yessin, executive director of ProtectMyPayCheck, said in a statement provided to TheDCNF. "Americans for Prosperity’s donation allows us to fight the unions’ attempt to roll back those freedoms, and jeopardize those jobs with their lawsuit."[25]

Federal Judge Overturns Hardin County Right to Work; County Will Appeal

Hardin County's local right to work ordinance was invalidated on February 3, 2016, in a ruling by U.S. District Court Judge David Hale. The ruling stated that only state governments had the authority to enact right to work laws.[26] County officials planned to appeal the ruling.[27]

Kentucky House Committee Passes Right to Work

The Kentucky House Committee passed HB 1, an ALEC-inspired Right to Work measure amid a gathering of protesters on January 4, 2017.[28]

See language from Kentucky's Right to Work bill alongside an ALEC model bill here.

Local Right to Work and Lawsuits in Illinois

The village board of Lincolnshire, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, passed a local right to work ordinance in December 2015. On February 18, 2016, a federal lawsuit was filed by four unions challenging the legality of the ordinance. One of the unions also filed a lawsuit in Lake County alleging that the village board had violated open meetings laws when it passed the ordinance. In January 2016 the Liberty Justice Center, a law firm affiliated with the Illinois Policy Institute, "entered into an agreement with the village hall...to provide Lincolnshire with pro-bono legal representation in its defense of the ordinance," according to the Chicago Tribune.[29] Lawyers with the Liberty Justice Center confirmed to the Chicago Tribune in April 2016 that they would represent Lincolnshire in the two lawsuits related to the ordinance.[30] At that time, the lawsuits had not been resolved.

Impacts of Right to Work Policies

Flaws in Studies Supporting Right to Work

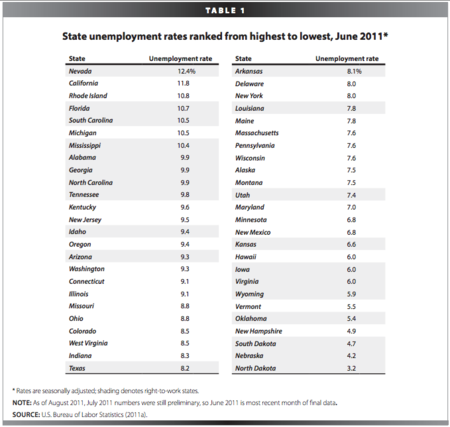

While advocates of "right-to-work" claim that the policies lower unemployment and lead to faster wage growth, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) has pointed out significant flaws in the studies they refer to, including not controlling for many other factors that directly impact a state's economy and aggregating data to make it appear that similar economic trends are evident in all "right to work" states. Such flaws confuse correlation with causation.[31] For example, the average unemployment rate in all states with right-to-work laws may be slightly lower than the average of all other states, but comparing individual states reveals that there is no relationship between unemployment rates and right-to-work laws.

- "Seven of the 10 highest-unemployment states are states with right-to work laws. How can that be true, if right to work is the path to low unemployment? [...] Indeed, both the highest and the lowest unemployment rates in the country are found in states with such laws. Clearly, then, something other than right to work explains relative growth rates in the states. [...]

- "The economic fortunes of the 22 states with right-to-work laws are mostly explained by the unique features of their economies and state economic development policies. Texas, for instance—the single largest right-to work state—has a very large oil and gas industry. Florida and Nevada have large tourism industries and attract large numbers of both young people and retirees drawn to the climate. It is factors such as these—along with a host of state policies other than labor law—that determine a state’s economic fortunes."[32]

Referring to a study by a State Policy Network member, the Rio Grande Foundation, University of New Mexico statistician Tamara Kay criticized the practice as "kindergarten math": "The numbers are averages. That's kindergarten math. No one can walk into the Anderson School of Business and say, 'Look at these averages,' and get a job. That makes no sense statistically. I was concerned that public policy was being made for bad math. [...] As I'm going to say today [to the committee], explaining averages is like saying there are higher birth rates where there are more storks, but that doesn't mean storks bring babies."[33]

Lower Wages and Benefits in Right to Work States

"Right to work" policies do appear to correlate with lower wages and benefits, even when other factors are controlled for. The EPI has found "The effect on the average worker—unionized or not—of working in a right-to-work state is to earn approximately $1,500 less per year than a similar worker in a state without such a law," and [34] Employers in "right to work" states are also less likely to offer pensions and health benefits.[32] A 2007 paper in the Review of Law and Economics concluded that "the number of businesses and self-employed are greater on average in right-to-work states, but employment, wages, and per-capita personal income are all lower on average in right-to-work states."[35]

Right to Work and Declining Union Membership

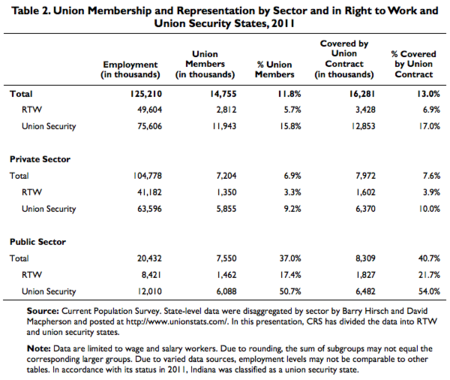

In a 2012 memo reviewing existing research for the Congressional Research Service, labor analyst Benjamin Collins found two trends regarding union membership rates and "right to work":

- "First, the union membership rate in union security states is nearly three times that of RTW states (15.8% vs. 5.7%). Second, the proportion of workers who are covered by a union contract but who are not members of the union is higher in RTW states than union security states. In RTW states, about 18% of the workers who are covered by a union contract are non-members (approximately 616,000 of 3.4 million). In union security states, this share is about 7% (about 910,000 of 12.8 million)."[36]

Right to work may also have an impact on worker safety. A University of Michigan study of fatality rates in the construction industry found that "higher levels of unionization equate with lower fatality rates" and that "unions are less effective at protecting member safety in right-to-work states." One theory suggested for these outcomes is that "RTW laws result in the underfunding of union safety training or accident prevention activities."[37]

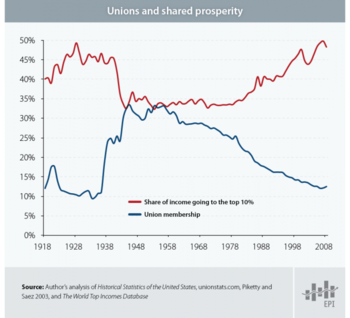

Income Inequality Rises as Union Membership Falls

Economist Paul Krugman has written that after World War II, labor unions played a key role in creating a broad middle class in the U.S.:

- "Everything we know about unions says that their new power was a major factor in the creation of a middle-class society. First, unions raise average wages for their membership; they also, indirectly and to a lesser extent, raise wages for similar workers, even if they aren’t represented by unions. Second, unions tend to narrow income gaps among blue-collar workers, by negotiating bigger wage increases for their worst-paid members."[38]

A 2011 peer-reviewed study by sociologists at Harvard University and the University of Washington calculated that between 1973 and 2007, "the decline of organized labor explains a fifth to a third of the growth in inequality—an effect comparable to the growing stratification of wages by education."[39]

Right to Work May Increase Profits, Stock Prices

The Congressional Research Service report notes that a few studies have found additional benefits to right-to-work:

- "A 2009 study by Stevans found that RTW had little effect on employment but did have a positive relationship with proprietors’ incomes. A 2000 study looked at the performance of stocks for companies based in Louisiana and Idaho during the periods when those states were initially passing their RTW laws in 1976 and 1986, respectively. This study evaluated the performance of these stocks on days where there was key movement in RTW legislation in the respective states and found that, relative to the larger market, stocks from companies based in these states increased 2% to 4%.3."[36]

Articles and Resources

Related SourceWatch Articles

- American Legislative Exchange Council

- American City County Exchange

- Berman & Co.

- National Federation of Independent Business

- National Restaurant Association

- National Right to Work Committee

- National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation

- U.S. Chamber of Commerce

- Institute for Legal Reform

External Resources

- Economic Policy Institute Right to Work Resources

- National Labor Relations Board

- The Center for Media and Democracy's Testimony on Right to Work, submitted to the Wisconsin State Assembly's Committee on Labor on March 2, 2015.

- "Walker's Wisconsin, a 'Laboratory for Oligarchs,'" Brendan Fischer, PR Watch, June 12, 2015; includes side-by-side comparisons of ALEC and state RTW bills.

- "Scott Walker and the Fate of the Union," Dan Kaufman, New York Times Magazine, June 12, 2015.

- "Wonkblog: What do ‘right-to-work’ laws do to a state’s economy?," Brad Plumer, The Washington Post, December 10, 2012.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Center for Media and Democracy, "Right to Work Act Exposed," ALEC Exposed project, accessed February 12, 2015.

- ↑ Jonas Persson, "National Right to Work Committee Attacks WI Workers with Hypocritical Zeal," Center for Media and Democracy, PR Watch, March 3, 2015. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- ↑ National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, "Right to Work FAQ," organizational press release, accessed February 16, 2015.

- ↑ Americans for Prosperity Wisconsin, Now is the Time for Right to Work, organizational website, February 20, 2015.

- ↑ National Labor Relations Board, "Employer/Union Rights and Obligations," government website, accessed February 16, 2015.

- ↑ Labor Management Relations Act, U.S. federal law, passed 1947.

- ↑ Communications Workers of America v. Beck, U.S. Supreme Court case, 1988.

- ↑ United Nations, "U.N. Declaration of Human Rights," Article 28, organizational document, December 10, 1948. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- ↑ Lisa Graves, Brendan Fischer, and Nick Surgey, "Koch-Fueled Playbook against WV Working Families Exposed by CMD," Center for Media and Democracy, PR Watch, February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Theresa Riley, "How Michigan’s Right-To-Work Law Came to Be," Moyers & Company, December 11, 2012. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Brendan Fischer, "ALEC-Inspired "Right to Work" Bill Back Again in Pennsylvania," Center for Media and Democracy, PR Watch, January 31, 2013. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Marry Bottari and Brendan Fischer, "Koch-Tied Group Pushes New Union-Busting Bill in Wisconsin," Huffington Post, December 3, 2014. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, Legislation tagged "ACCE", search results, February 11, 2015.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, "Local Right to Work Ordinance," organizational document, January 9, 2015. Accessed February 11, 2015.

- ↑ Brendan Fischer, "An Embattled ALEC, Buoyed by Election Results, Lays Blueprint for 2015," Center for Media and Democracy, PR Watch, November 17, 2014. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Shaila Dewan, "Foes of Unions Try Their Luck in County Laws," The New York Times, December 18, 2014.

- ↑ Sean Higgins, "Right-to-work push goes local," Washington Examiner, September 1, 2014. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ James Sherk and Andrew Kloster, "Local Governments Can Increase Job Growth and Choices by Passing Right-to-Work Laws," report, Heritage Foundation, August 26, 2014. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Brendan Fischer, "Republicans Call for Imposing ALEC Zones on Poorest Neighborhoods of Milwaukee," Center for Media and Democracy, PR Watch, February 2, 2015. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Shaila Dewan, "Foes of Unions Try Their Luck in County Laws," New York Times, December 19, 2014. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Mary Spicuzza, Jason Stein and Patrick Marley, "Assembly sends Wisconsin's right-to-work bill to Scott Walker," Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, March 6, 2015. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- ↑ Stan Greer, "Kentucky Court: State ‘Political Subdivisions’ Have ‘No Power’ to Bar Forced Union Dues," National Right to Work Committee, blog post, December 23, 2014. Archived by Kentucky State AFL-CIO, accessed March 6, 2015.

- ↑ Joseph Gerth, "Right-to-work legislation still an issue," Courier-Journal, February 12, 2015.

- ↑ Jack Brammer, "Labor unions file court challenge to Hardin County's 'right-to-work' ordinance," Lexington Herald-Leader, January 15, 2015.

- ↑ Connor D. Wolf, "First Of Its Kind Right-To-Work Fight Gets $50,000 Boost," The Daily Caller, July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Adam Beam, "Federal judge overturns local right-to-work laws in Kentucky," Lexington Herald Leader/Associated Press, February 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Hardin County officials say they will appeal a federal judge's ruling that overturned a local law banning mandatory union membership," Daily Journal/Associated Press, February 4, 2015.

- ↑ WKYT, Abortion, right-to-work among first bills considered in legislative session, WKYT, January 4, 2017.

- ↑ Ronnie Wachter, "Lincolnshire faces state and federal lawsuits over right-to-work law," Chicago Tribune, February 23, 2016.

- ↑ Ronnie Wachter, "Conservative think tank confirms it will defend Lincolnshire in two lawsuits brought by unions," Chicago Tribune, April 19, 2016.

- ↑ Sylvia A. Allegretto and Gordon Lafer, "What’s wrong with ‘right-to-work': Chamber’s numbers don’t add up," Economic Policy Institute, February 28, 2011. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Gordon Lafer, "http://s2.epi.org/files/2011/BriefingPaper326.pdf ‘RIGHT TO WORK’: The wrong answer for Michigan’s economy," briefing paper, Economic Policy Institute, September 15, 2011. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- ↑ Dan Mayfield, "Professor calls right-to-work study 'kindergarten math'," Albuquerque Business First, February 17, 2015. Accessed February 19, 2015.

- ↑ David Madland, Karla Walter, and Ross Eisenbrey, "Right-to-Work 101," report, Economic Policy Institute, February 2012. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- ↑ Lonnie Stevans, "The Effect of Endogenous Right-to-Work Laws on Business and Economic Conditions in the United States: A Multivariate Approach," Review of Law and Economics, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2009. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Benjamin Collins, "Right to Work Laws: Legislative Background and Empirical Research," Congressional Research Service, federal government publication, December 6, 2012. Archived by Cornell University ILR School. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Roland Zullo, "Right-to-Work Laws and Fatalities in Construction," working paper, University of Michigan Institute for Research on Labor, Employment, and the Economy, March 2011. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Paul Krugman, "The Conscience of a Liberal," Norton & Company, 2009, p. 51. Accessed via Google Books, February 13, 2015.

- ↑ Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld, "Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality," American Sociological Review, Vol. 76, No. 4, 2011. Accessed February 13, 2015.