Adecco Group

The Adecco Group is a publicly-traded (OTCMKTS:AHEXY) (ADEN:VX) for-profit international company headquartered in Switzerland that provides temporary staffing services around the world. It had 31,500 full-time employees and over 650,000 "associates" (temp. workers) in 2014, according to its website. In addition to temp. staffing, it also offers outsourcing and consulting services.[1] It had around 5,100 branches in more than 60 countries and territories around the world as of its 2013 annual report.[2]

Adecco's 2013 revenues totaled $24.36 billion, and it reported a net income of $695.8 million for the same year.[3]

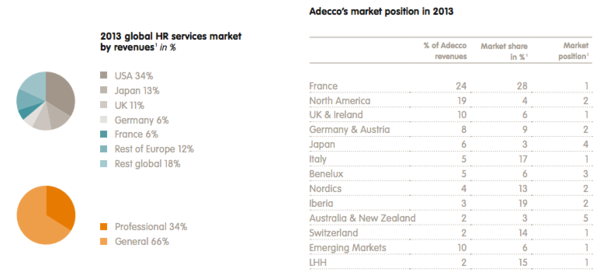

Adecco's largest market is France, which generated 24 percent of the company's revenues in 2013, and where the company's business is dominated by industrial staffing. Its share of the U.S. market in 2013 was four percent, and North America contributed about 19 percent of the company's annual revenues in 2013. Slightly over half of its business in North America is comprised of professional staffing, with the remaining business roughly split between office and industrial staffing.[4]

Contents

Replacing Middle-Class Manufacturing Jobs with Low-Wage Temp Work

Temporary employment is increasingly common for U.S. workers. The United States had more than 2.7 million temp workers in 2013, and nearly one-fifth of the growth in jobs since the 2008 financial crisis has been in the temp. sector. The American Staffing Association (the temp. sector's trade association) estimates that one-tenth of workers find jobs through staffing agencies like Manpower each year. Pro Publica reports that "temporary work has become a mainstay of the economy," filling positions "in the supply chain of many of America's largest companies -- Walmart, Macy's, Nike, Frito-Lay," etc.[5] Temporary workers earn an average of 25 percent less than equivalent permanent workers.[5]

One reason why manufacturing jobs in the United States are now in the bottom half of all jobs in terms of pay is an increased reliance on temporary workers, as detailed by a 2014 report by the National Employment Law Project (NELP). According to NELP:

- "About 14 percent of auto parts workers are employed by staffing agencies today. Wages for these workers are lower than for direct-hire parts workers. [...] Estimates based on U.S. Census Bureau data [...] indicate that auto parts workers placed by staffing agencies make, on average, 29 percent less than those employed directly by auto parts manufacturers."[6]

Temp Agencies Skirt Union Opposition by Branding as "Women's Work"

Being founded at a time when labor unions were at their most influential, temp. agencies like Adecco's pre-merger predecessors and Kelly Services avoided union opposition by strategically presenting temporary work as "women's work" in advertising, which suggested that temps were housewives working for extra spending money, according to Erin Hatton, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the State University of New York, Buffalo, writing for the New York Times.[7]

With the help of these gender stereotypes, temp. agencies established "a new sector of low-wage, unreliable work" that was exempt from many of the protections won by labor unions in other parts of the economy.[7]

By the early 1970s, temp. agencies were promoting what they called "a lean and mean approach to business that considered workers to be burdensome costs that should be minimized," with the help of ads like one by Kelly Services advertising "The Never-Never Girl," who "Never takes a vacation or holiday. Never asks for a raise. Never costs you a dime for slack time. (When the workload drops, you drop her.) Never has a cold, slipped disc or loose tooth. (Not on your time anyway!)"[7][8]

Other Controversies

Criticism from European Union over Low Pay, Alleged Strike-Breaking

Adecco has come under criticism in Norway, Spain, and France for its low wages and for allegedly providing temp. workers to companies whose workers were on strike.[9][10]

Labor groups and their supporters have engaged in a number of actions targeting Adecco for providing labor to companies whose workers were on strike, including Finnair[11] and the Asea Boveri Brown company in Cordoba, Spain.[12][13]

The Spanish newspaper El Mundo reported in 2013 that Finnair had contracted with Adecco for 210 workers in case of a strike.[14]

Lawsuit over Sexual Harassment and Retaliation Settled (2010)

As described in a report by the National Employment Law Project, in June 2010 Adecco "settled a sexual harassment and retaliation lawsuit based on discriminatory treatment that female Adecco workers experienced working for Adecco's client, Pittsburgh Plastics Manufacturing. The EEOC argued that Adecco knew about the sexual harassment its workers faced but continued to send female workers to work under the alleged harasser's supervision, as well as firing one worker who complained about the harassment. The EEOC also won $79,500 from Pittsburgh Plastics in a related action."[15]

Accused of Stealing Blogger's Brand and Concept for Marketing Campaign (2013)

Adecco was embroiled in a scandal in 2013 when blogger Turner Barr, creator of the site "Around the World in 80 Jobs," accused the company of copying his brand name and blog concept for use in a marketing campaign, also called "Around the World in 80 Jobs."[16] Adecco then proceeded to try to shut down Barr's blog in an attempt to assert trademark rights, even though Barr had been operating his blog for two years prior to Adecco's marketing campaign, according to the Daily Dot. Followers of the scandal, including in forums on the popular site Reddit, put pressure on Adecco, eventually leading the company to come to an agreement with Barr.[17][18]

Political Activity

Corporate Subsidies

In its 2010 Corporate Social Responsibility Report, Adecco stated:

- "The Adecco Group does not receive any material financial subsidies from governments. However, some of our societal activities, at a local level, are subsidised. These include labour integration projects and joint programmes with governmental organisations. These subsidies obviously do not assist us in our ordinary business, but help, to a certain degree, to remunerate our efforts to support governments in helping disadvantaged and unemployed people get into the labour market."[19]

Other data suggest, however, that Adecco has received significant subsidies that help its bottom line, including tax breaks from local and state governments in the United States and national governments in Europe.

The Corporate Subsidy Tracker website run by the non-profit Good Jobs First reports at least $1,076,509 in subsidies given to Adecco between 1997 and 2012 in three states: Florida, New York, and California.[20]

France introduced a tax cut in 2013, increasing in 2014, that "effectively cuts payroll taxes on the salaries of employees that are at or just above the minimum wage, and the subsidy goes straight on to the bottom line of staffing firms." While the cut was not targeted only at Adecco, it benefited the company's bottom line at an expense to French taxpayers. The company reported in May 2014 that the tax cut had contributed to an increase in its profit margin in France.[21] Operations in France generated 24 percent of Adecco's total revenues in 2013, making it the company's largest market.[22]

Adecco Begins Lobbying in Florida, Secures $2 Million in Concessions

Adecco was set to gain "economic concessions worth about $2 million, or more than $10,000 per job, by moving 185 positions from Melville[, Tennessee] to its new North American headquarters in Jacksonville," Florida, as reported by Newsday a( Long Island paper) in March 2014. Jacksonville Mayor Alvin Brown planned to introduce a local ordinance to the city council calling for the company to be designated a "qualified target industry" in a "high impact sector" by the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity. According to Newsday, the planned incentives were to include:

- "$1.11 million from the Florida Qualified Targeted Industry Tax Refund program. Eighty percent of that would be paid by the state with a 20 percent match from Jacksonville";

- "$370,000 from Florida Gov. Rick Scott's Quick Action Closing Fund and a match of up to $185,000 from the Countywide Economic Development Fund"; and

- "$333,000 from Florida's Quick Response Training Fund."[23]

Adecco's registered lobbyists in Florida in 2014 were Brian D. Ballard, Bradley S. Burleson, and William Gregory Turbeville.[24][25]

Florida lobbying records do not show any lobbyists registered with Adecco for 2013, suggesting that it started lobbying in Florida in 2014.[26][27]

Ballard is a lobbyist for Ballard Partners, which lobbies on behalf of dozens of organizations in Florida, including Xerox, the United States Sugar Corporation, Verizon, Oracle, Uber, Deloitte, and a number of healthcare-related groups including Corizon Health. (Corizon won a lucrative contract to oversee state prison health care in 2011 and since then has been criticized for high rates of malpractice and inmate death.[28])

Federal Lobbying

Adecco reported $60,000 in lobbying expenses at the federal level in the United States in 2003. It contracted with Morrison Public Affairs Group for lobbying services on immigration and labor, antitrust, and workplace issues.[29]

History and Philosophy

According to its website:

- "The Adecco Group is the result of over 50 years' expansion and growth by acquisitions around the world. The founding companies, Adia and Ecco, merged in 1996 to form the global leader."[30]

In its own publications, Adecco presents itself as providing opportunities, training, and flexibility to workers:

- "...[W]e offer legally recognised and regulated work opportunities, facilitate on-the-job training and enhanced occupations and geographic mobility. HR services companies also create stepping-stone opportunities for under-represented groups to gain work experience and to secure complementary incomes (e.g. students, part-timers, retirees)."[2]

According to Adecco CEO Patrick De Maesenaire, "Work is a basic need; it should be a basic right for all people."[31]

Questionable Help to the Unemployed

Unemployed people who are seeking work often face barriers that have little to do with their skills and training, however. An Adecco executive has said on the record that in the current high-unemployment environment, many firms are simply refusing to consider applicants who are not currently employed, as a 2011 report by the National Employment Law Project notes:

- "Rich Thompson, vice president of learning and performance for Adecco Group North America, the world's largest staffing firm, told CNNMoney.com last June that companies' interest only in applicants who are currently working 'is more prevalent than it used to be…I don't have hard numbers,' he said, 'but three out of the last four conversations I've had about openings, this requirement was brought up.'"[32]

Adecco itself has used the common practice of excluding applicants with criminal records, even when offenses may have little to do with the requirements of the job itself. According to a report by the National Employment Law Project:[33]

- "A final category of ads routinely posted on Craigslist limits exclusions to convictions within a specific, albeit protracted timeframe. While less restrictive than a lifetime ban, even these more limited exclusions can be problematic. The ads' specified time period may be excessive, and they fail to address the relationship between the offense and job. The following advertisement exemplifies this type of exclusion:

- "'Be able to pass a 7 year criminal background check (no felonies, no misdemeanors)' - Job ad for Forklift Operator, Sept. 8, 2010, Adecco USA (70,000 employees in the United States...).

- "An absolute ban of applicants with convictions during the last seven years violates Title VII. For example, a job candidate with an isolated shoplifting or vandalism conviction from five years ago does not have a record that reflects on her ability to safely and effectively operate a forklift as required for this job. Nor is a five- or six-year-old conviction sufficiently recent in all cases to pose a security threat on the job."[33]

Personnel

CEO Patrick De Maeseneire

Patrick De Maeseneire has been CEO of Adecco Group since June 2009. His total compensation in 2013 was SFr.6,072,310 (about $6.3 million).[34]

De Maeseneire had previously worked in managerial positions for Adecco from 1998 to 2002, then served as CEO of the chocolate manufacturer Barry Callebaut from 2002 to 2009, when he returned to Adecco as CEO. He has also held senior positions at the resort hotel chain Sun International, Apple Inc, Wang, and Arthur Andersen Consulting.[35]

In a message on Adecco's website, De Maesenaire states, "The importance of work and what we do to help people find jobs cannot be overstated. Work is a basic need; it should be a basic right for all people."[31]

In general, De Maesenaire reportedly favors policy and law changes that would increase the flexibility and mobility of the workforce. For example, in a 2014 interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, he approved of Italian Premier Matteo Renzi's attempts to change Italy's labor laws, including to make it easier for companies to fire workers:

- "It's going in the right direction," de Maeseneire said. "I think it's a signal to the political environment that reforms are absolutely needed here in order to get people back to work."[36]

De Maesenaire also reportedly appears to hold the view that a significant factor in unemployment is an alleged mismatch between skills needed by employers and the training prospective workers have. He has lauded countries that "foster and develop locally available talent by making their labor markets more flexible, by investing in lifelong learning and by promoting geographical mobility" in a Huffington Post article published under his byline.[37]

In the same essay, he notes that youth unemployment in Spain and Greece was over 50 percent, implying that a lack of training is the primary culprit for the poor job prospects of youth.[37]

De Maeseneire was born in 1957 and is a Belgian citizen. He holds the title of Baron, granted in 2007 by King Albert II of Belgium.[35]

Executive Committee

As of April 2015:[38]

- Patrick De Maeseneire, CEO

- Dominik de Daniel, CFO

- Mark De Smedt, Chief Human Resources Officer

- Sergio Picarelli, Chief Sales Officer

- Alain Dehaze, Regional Head of Finance

- Robert P. Crouch, Regional Head of North America

- Martin Alonso, Regional Head of Northern Europe

- Christophe Duchatellier, Regional Head of Japan & Asia

- Andreas Dinges, Regional Head of Germany & Austria

- Federico Vione, Regional Head of Italy, Eastern Europe & India

- Enrique Sanchez, Regional Head of Iberia & South America

- Peter Searle, Regional Head of UK & Ireland

Board of Directors

As of April 2015:[39]

- Rolf Dörig, Chairman

- Andreas Jacobs

- Dominique-Jean Chertier

- Alexander Gut

- Didier Lamouche

- Thomas O'Neill

- David Prince

- Wanda Rapaczynski

Contact

Route De Bonmont 31

Chéserex, Vaud, 1275 Switzerland

Phone: +41-223691222[40]

Contact Form: http://www.adecco.com/en-US/About/Pages/Contact.aspx

Web: http://www.adecco.com/en-US/

Resources and Articles

Related SourceWatch Articles

References

- ↑ Adecco, "Who We Are and What We Do," organizational website, accessed November 5, 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Adecco, "Adecco Group Annual Report 2013," organizational report, accessed November 5, 2014.

- ↑ Bloomberg Businessweek, Adecco, corporate profile, accessed November 5, 2014.

- ↑ Adecco, Review of Main Markets, 2013 Annual Report, accessed November 12, 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Michael Grabell, "The Expendables: How the Temps Who Power Corporate Giants Are Getting Crushed," Pro Publica, June 27, 2013.

- ↑ Catherine Ruckelshaus and Sarah Leberstein, National Employment Law Project, "Manufacturing Low Pay: Declining Wages in the Jobs That Built America’s Middle Class," organizational report, November 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Erin Hatton, "The Rise of the Permanent Temp Economy," The New York Times, January 26, 2013.

- ↑ Kelly Services, "The Never-Never Girl," advertisement, 1971, archived on Document Could by Krista Kjellman Schmidt, ProPublica, accessed April 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Europe: Adecco under fire from unions in Norway and Spain," Staffing Industry Daily News, January 23, 2012.

- ↑ "France: Unions call for strike at Adecco," Staffing Industry Daily News, April 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Finnair plans to hire strike-breakers from Spain," Finland Trade Union News, August 22, 2013.

- ↑ International Workers Association, "Bristol and Spanish workers picket multi-national strike breakers Adecco," Solidarity Federation news release, January 24, 2012.

- ↑ Martin O'Neill, "Glasgow Picket Against Adecco Supplying scabs at ABB Factory Cordoba Spain," IndyMedia Scotland, January 21, 2012.

- ↑ César Urrutia, "Esperamos que muchos de vosotros vengáis si hay una huelga," El Mundo, September 20, 2013.

- ↑ Rebecca Smith and Claire McKenna, National Employment Law Project, "Temped Out: How the Domestic Outsourcing of Blue-Collar Jobs Harms America’s Workers," organizational research report, July 2014.

- ↑ Turner Barr, "How I Got Fired from the Job I Invented," Around the World in 80 Jobs blog, June 20, 2013.

- ↑ Tim Sampson, "Turner Barr 'Around the World in 80 Jobs' blogger says company stole his idea," Daily Dot, June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Adecco settles controversy with blogger," Crain Staffing Industry Daily News, June 28, 2013.

- ↑ Adecco, "Corporate Social Responsibility; Economic Indicators," company report, accessed November 12, 2014.

- ↑ Good Jobs First, Adecco, Subsidy Tracker website, accessed November 12, 2014.

- ↑ "RPT-'Sick man' France offers healthier outlook for staffing firms," Reuters, July 30, 2014.

- ↑ Adecco, Review of Main Markets, 2013 Annual Report, accessed November 12, 2014.

- ↑ Ken Schachter, "Adecco could reap $2M with staffing move to Florida," Newsday, March 25, 2014.

- ↑ Florida Legislature, 2014 Legislative Registration by Principle Name, Online Sunshine Lobbying Database, accessed November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Florida Legislature, 2014 Executive Branch Registration by Principle Name, Online Sunshine Lobbying Database, accessed November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Florida Legislature, 2013 Legislative Registration by Principle Name, Online Sunshine Lobbying Database, accessed November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Florida Legislature, 2013 Executive Branch Registration by Principle Name, Online Sunshine Lobbying Database, accessed November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Mary Bottari and Jonas Persson, "Inmates Die in Droves After Governor Rick Scott Outsources Prison Healthcare," Center for Media and Democracy, PR Watch, October 16, 2014. Accessed November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Center for Responsive Politics, Adecco, Open Secrets lobbying report, accessed November 12, 2014.

- ↑ Adecco, History, corporate website, accessed July 29, 2012.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Adecco, About Adecco, corporate website, accessed November 5, 2014.

- ↑ National Employment Law Project Statement of the National Employment Law Project Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions," organizational U.S. Senate testimony, December 6, 2011.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Michelle Natividad Rodriguez and Maurice Emsellem, National Employment Law Project, "65 Million 'Need Not Apply': The Case for Reforming Criminal Background Checks for Employment," organizational research report, March 2011.

- ↑ Adecco, Bloomberg Businessweek executive profile, accessed November 5, 2014.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Adecco, Executive Committee], corporate biography, accessed November 5, 2014.

- ↑ Alessandra Migliaccio and Flavia Rotondi, "Italian Premier Renzi Moving in Right Direction, Adecco CEO Says," Bloomberg Businessweek, September 25, 2014.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Patrick De Maesenaire, "Is Talent the Future Currency?," Huffington Post, January 21, 2014.

- ↑ Adecco, Executive Committee, corporate website, accessed April 14, 2015.

- ↑ Adecco, Board, corporate website, accessed April 14, 2015.

- ↑ Adecco, Hoovers, accessed April 2015.