The Imperial Presidency

The Imperial Presidency by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. was written in 1973.

This book details the history of the Presidency of the United States from its conception by the Constitutional Founders, through the late twentieth century. The author wrote the Imperial Presidency out of two concerns; first that the US Presidency was out of control and second that the Presidency had exceeded the Constitutional limits.[1] A presidency becomes imperial when it relies on powers beyond those allowed by the Constitution. The Constitution established three separate branches of government not for efficiency but to avoid the arbitrary exercise of power. The government outlined by the Constitution was to replace and improve upon the imperial executive government of British King George III.[2] The book links the President’s accumulation of foreign powers during wartimes to the accretion of domestic powers.

The Constitution and its authors determined that the power to initiate a war belonged to the Congress. The President had the responsibility to conduct ongoing wars and ongoing foreign relations and respond to sudden attacks if the Congress was not in session.[3] As the United States of America became a great world power, and then a superpower, the Presidency acquired more war powers despite the Constitution. This reduced the Congress’ powers and the separation of powers, which is necessary to avoid the arbitrary use of power.[4]

Through various means, Presidents subsequently acquired powers beyond the limits of the Constitution. The daily accountability of the President to the Congress, the courts, the press and the people has been replaced by an accountability of once each four years during an election. These changes have occurred slowly over the centuries so that that which appears normal differs greatly from what was the original state of America.[5]

Contents

1793 - 1896

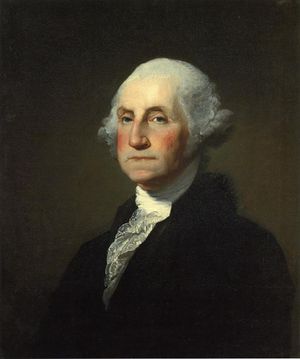

In 1793, President George Washington unilaterally determined that the new American Republic was neutral in the war between Kingdom of Great Britain and France during the French Revolutionary Wars. Alexander Hamilton supported this action while Thomas Jefferson and James Madison objected. The proclamation prohibited American citizens from assisting either Britain or France. However, grand juries refused to enforce this proclamation.[6]

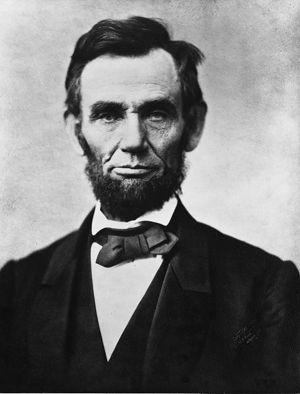

In 1846, to annex Texas, President James K. Polk sent troops between Texas and Mexico, provoking a war. Polk then manipulated Congress to recognizing a state of war. Congressman Abraham Lincoln stated if this was allowed then a President could arbitrarily make war just as monarchs do, and that the Constitutional Convention recognized that war-making power must not be in the hands of one man.[7]

During the American Civil War, Lincoln assumed war powers as commander-in-chief of the military however he made no claim that the Constitution allowed him these powers. Without Congressional authorization, Lincoln unilaterally expanded the military, suspended habeas corpus, arrested citizens, proclaimed martial law, seized property, censored newspapers, and emancipated slaves. Lincoln justified these actions to preserve the country rather than the Constitution.[8] However he stated that these Presidential war powers would cease to exist once the national emergency, the Civil War ended.[9]

After the Civil War, in 1866, the Supreme Court asserted that the Constitution was the law of the land in war and peace and that government powers can not exceed those granted by the Constitution.[10] In 1867, the Supreme Court stated that the President must carry out the law and could not break the law. Presidential power was deflated following the Civil War.[11]

With the Spanish American War, in 1898, the United States of America became a great power and also Presidential power expanded.[12] In 1900, President William McKinley sent 5000 troops to China (see Boxer Rebellion) for political purposes without Congressional approval.

1900 - 1949

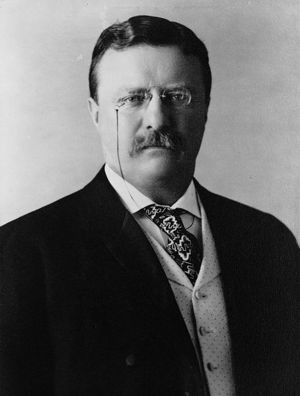

President Theodore Roosevelt sent troops in many Caribbean countries and established a new government in a few also without Congressional approval.[13] This included actions in Colombia, Panama, Honduras, Dominican Republic and Cuba.

In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge sent 5000 troops to Nicaragua without Congressional approval. He was considered a strict constructionist in other matters.[14]

In 1939, after the start of World War II in Europe, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a limited national emergency. The concept of limited national emergency seems to rest on implied and assumed powers of the President and the assertion of it by the President. On May 27, 1941, Roosevelt had determined that the nation was in a state of unlimited national emergency. Congress ended the national emergency in 1947, two years after the end of World War II. National Emergency powers are defined as “the President may seize property, organize and control the means of production, seize commodities, assign military forces abroad, institute martial law, seize and control all transportation and communication, regulate the operation of private enterprise, restrict travel, and, in a variety of ways, control the lives of United States citizens.” Congressional Research Service Reports 98-505.

In 1942, Roosevelt threatened Congress that if a provision of the Emergency Price Control Act were not repealed within three weeks that he would block its implementation. World War II was used to justify this threat. Like Lincoln, he added that when the war ended, the war powers would return to the people. Congress repealed the provision and the threat was not acted upon.[15]

Over the history of the US, a pattern emerged that the President assumed greater powers during the emergency. After the emergency had passed, then Congress would assert itself. This occurred after the Civil War and World War I but after World War II Congress did not assert itself as much because of the Cold War. In 1946 Democratic President Harry S. Truman wanted the Republican Congress to approve aid to Greece and Turkey. He found that by turning a reasonable program into the Truman Doctrine and exaggerating the issue, he got the appropriation.[16]

1950 - 1964

In 1950, Truman had sent troops to the Korean War without Congressional approval.[17] In 1952, Truman feared a national strike by the steel industry would impair the military’s ability to fight the Korean War. He ordered the Secretary of Commerce to seize and operate the steel mills without Congressional approval.[18] The Supreme Court found the actions unconstitutional. The majority of justices stated that the Commander-in-Chief clause of the Constitution did not apply to domestic matters and that the President must comply with existing laws on this matter.[19]

By 1952, Truman increased the Armed Services to 3.6 million and that by itself resulted in an increase in presidential power. Before this only Lincoln had increased the Army without Congressional approval. The addition of 50 treaties increased presidential responsibilities and power in the 1950s.[20] The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) under the direction of the President overthrew the governments of Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954). The CIA attempted but failed to overthrow the government of Indonesia. The CIA installed new governments in Egypt (1954) and Laos (1959). Also the CIA organized Cuban refugee to overthrow the Cuban government (1960-1961).[21] The Presidency’s control of foreign policy vastly increased while constitutional separation of powers decreased.[22] In the decade after the Korean War, most liberal and conservative members of Congress agreed on Presidential control of foreign policy.[23]

The Cuban Missile Crisis showed that independent and unilateral presidential action in extreme circumstances is at times required. However this was a unique situation of threat and secrecy in the nuclear age and should not have been used to justify the imperial Presidency.[24]

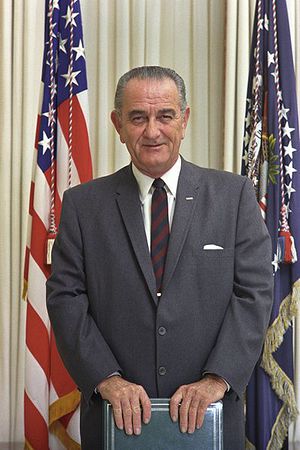

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson sent 22,000 troops to the Dominican Republic without Congressional approval. The same year he sent combat troops for the first time into Vietnam. This war lasted the longest in US history and resulted in the fourth largest number of US deaths after the Civil War and the two World Wars. The Tonkin Gulf resolution authorized the President to use the military, as he required. This was transfer of war powers from the Congress to the President.[25] Lincoln believed that if the President could bring the country to war then he held the power of a king. In 1970, President Richard Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia, without Congressional approval. By 1971, the Tonkin Gulf resolution was revoked by Congress. However the Vietnam War continued solely due to Nixon’s authority.[26] Nixon claimed war powers as Commander-in-Chief of the military. Before Lincoln that title only indicated the topmost officer of the armed forces. Lincoln used it for greater authority and so could future Presidents in the event of a civil war. Nixon justified his authority to order the invasion of Cambodia with his Commander-in-Chief title.[27]

1965 - 1973

Cambodia and Laos were neutral countries and not a threat. Laos was unilaterally and secretly bombed from 1964 to 1973.[28] In 1971, Congress passed an amendment to the defense-spending bill to terminate all military operations in Indochina (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam) and Nixon signed it but he continued the Indochina War.[29] Under Nixon Congress had no war powers.[30] By 1971, Congress discovered seven secret bases, and 32,000 troops in Thailand. Nixon had made defense agreements with Thailand and the Federal Government was secretly funding the Ethiopian Army, all without Congress’ knowledge or approval. The Constitution requires 2/3rd Senate approval of treaties before they become law.[31]

The imperial Presidency was created in response to foreign policy issues. This resulted in the exclusion of the Congress, the press, the public and the Constitution in foreign policy decisions. Once established, the imperial Presidency then expanded into domestic issues.[32] Starting in 1947, Presidential power over the federal budget with slight modifications by Congress gave the President important controls over the economy and social priorities.[33] Strong Presidents should have strong-minded advisors.[34]

Nixon dismissed the opinions of the public, the press, and foreign nations. He used price controls, tax relief, and subsides, tariffs, import quotas and fiscal policy to manage the economy. These economic powers were used to reward economic sectors that supported his actions and punish those sectors that opposed his actions. Rather than veto Congressional legislation that he opposed, he would impound the funds.[35]The only option the Constitution allows if President opposes a law is the veto. The Constitution empowers the Congress to determine the level of spending, not the President. The President is not allowed to selectively enforce laws, which Nixon did.[36] Nixon's Presidential model resembled the plebiscitary Presidency. Plebiscitary democracy is defined as where a leader is elected but once elected has almost all of the power. See Bush's Plebiscitary Presidency Another explanation of the Nixon model would be a personal dictatorship or an elective kingship under the Constitution where the President represents the democratic majority and any opposition is considered antidemocratic. Public responses are limited to voting during elections.[37]

In 1970, Nixon has authorized investigating peaceful protesters but found nothing. Agents of the Treasury Dept. went to public libraries to examine the book borrowing records of citizens. Breaking and entering was authorized by Nixon to investigate suspects. The National Security Agency was authorized to monitor conversations of citizens making international phone calls. Citizens’ letters were opened and copied.[38] Nixon authorized his own private outfit, which burglarized, wiretapped, bugged, and used secret agents and political blackmail contrary to the laws and Constitution.[39] The Watergate scandal was the most public part of these activities.[40]

Nixon claimed that the President was not required to obey certain laws. He nearly succeeded but for the actions of hardline opponents.[41] The courts, the press, executive agencies, and Congress cannot take credit for blocking the imperial presidency however they benefited from less powerful Presidency.[42] Blocking the imperial presidency did not change the conditions that made it possible.[43]

Problems and solutions

Foreign policy challenges the separation of powers. The Presidency reigns supreme in foreign policy.[44] That one person should not commit the nation to war nor continue a war is valid and Constitutional.[45] However usually those raising Constitutional questions do so for political reasons.[46]

Schlesinger writes, “The weight of messianic globalism was indeed proving too much for the American Constitution. If this policy were vital to American survival, then a way would have to be found to make it constitutional; perhaps the Constitution itself would have to be revised. In fact, the policy of indiscriminate global intervention, far from strengthening American security, seemed rather to weaken it by involving the United States in remote, costly and mysterious wars, fought in ways that shamed the nation before the world and, even when thus fought, demonstrating only the inability of the most powerful nation on earth to subdue bands of guerrillas in black pajamas. When the grandiose policy did not promote national security and could not succeed in its own terms, would it not be better to pursue policies that did not deform and disable the Constitution?” on page 299.

Congress and the President should reduce US interests abroad and lower military spending. This would lower the pressure on the national government and allow Congress to act.[47] Only two requirements would be needed to resolve the situation. First, the President must report to Congress immediately with all information and justification when troops were sent into battle and continue while reporting during the conflict.

Second, a joint declaration by Congress at anytime can terminate the conflict.[48] Another option during peacetimes is allowing Congress to control troops overseas.[49] The history of US war-making in the 20th century suggested that it was a shared power between the President and the Congress.[50]

The CIA is exempt from Congressional oversight and spending rules and regulations.[51] If Congress wished to bring the CIA under control, it could prohibit covert operations except during wartime.[52]

National emergency powers allow the President unilaterally to control any business activity or person within the country. Once a national emergency is proclaimed, it should get Congressional approval within 30 days if it is to remain in effect. A joint resolution of Congress should be able to cancel a national emergency.[53] The national emergency power can only be used when the nation is at risk of being lost. Only the Civil War, WWII and possibly the Cuban Missile Crisis qualify as true national emergencies. The national emergencies claimed by Jefferson, Truman and Nixon do not meet this standard.[54]

Foreign policy conducted by the President only is self-defeating if the people do not support it. If the Congress does not understand the foreign policy neither will the people.[55]

Presidential secrecy can be justified with either claims of national security or executive privilege. These claims do not rely on statues but they do depend on unchecked executive judgment. National security claims were developed from the classification of documents. Executive privilege claims were originally used by the President to protect personal communications from Congress.[56]

As early as 1795 the following pattern recurred. First the President kept some facts secret when facing difficult foreign policy decisions. A citizen discovered these facts and felt it was their duty to make these facts public. A member of the free press then would disclose the facts.[57] By the 1950s, Congress was at odds with the military over secrecy. Reports on bows and arrows, shark repellent, and monkeys in outer space were classified secrets.[58] By 1972 some newspaper clippings were deemed to be secret.[59] In 1966, a secret CIA memo complained that the publication of classified secrets could be successfully defended with the ‘public had a right to know’ argument.[60]

Secrecy appeals to leaders of nation that value openness and accountability. The power to withhold, leak and lie about information seems fleeting when the information is publicly revealed. ‘If you only know what we know’ remarks are temping for officials.[61] The power to withhold and leak leads to the power to lie. Examples of this were found in President Eisenhower CIA actions, President Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs and Vietnam actions, President Johnson’s Vietnam operations, and President Nixon’s Cambodia bombing.[62] Between 1965 and 1975, the number of US citizens that believed their government was lying had greatly increased due to the government’s secrecy system.[63] Perhaps the US would have benefited from leaks about the CIA in the fifties, the Bay of Pigs operation, war crimes in Vietnam, and wars in Laos and Cambodia by avoiding these disasters.[64]

Congressional members often prefer to be poorly informed to avoid responsibility and accountability for foreign policies.[65] Although many are shocked when secret foreign policy documents are revealed, the information was often previously published. Congress could be better informed if it wished.[66]

The revolutionary transformation to the plebiscitary Presidency is a Presidency that is accountable only during elections or impeachment rather than daily to the Congress, the press and the public. Plebiscitary democracy is defined as where a leader is elected but once elected has almost all of the power. See Bush's Plebiscitary Presidency The plebiscitary President would govern by decrees such as executive orders.[67]

The Nixon administration was unique in the extent of probable criminal offences it committed. Burglary, forgery, illegal wiretapping and electronic surveillance, perjury, obstruction of justice, destruction of evidence, tampering with witnesses, giving and taking bribes, and conspiracy to involve government agencies in illegal actions. Nixon denied knowledge about these actions. Nevertheless he was found officially responsible for these actions.[68]

In an effort to rein in the imperial Presidency, Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina proposed that Congress have the ability to veto executive agreements within sixty days. Executive agreements are used by Presidents to make international arrangements without involving Congress. If enacted it would change the balance of power between the Presidency and Congress as well as affecting foreign policy decisions.[69]

A balance of power can be achieved when all great decisions are shared decisions. Although shared decisions may often be wise, they are always democratic.[70] Great Presidents understood that their rule required the consent of the Congress, the press, and the public.[71]

President Nixon's errors resulted in the expansion and abuse of Presidential power. If future Presidents govern by decree then impeachment would be necessary to rein in the Presidency and support the Constitution. With a constitutional Presidency, any actions by a President’s administration that are illegal or unconstitutional must be exposed and punished. Schlesinger writes “A constitutional Presidency, as the great Presidents had shown, could be very strong Presidency indeed. But what kept a strong President constitutional, in addition to checks and balances incorporated within his own breast, was the vigilance of the nation. Neither impeachment nor repentance would make much difference if the people themselves had come to an unconscious acceptance of the imperial Presidency. The Constitution could not hold the nation to ideals it was determined to betray.”[72]

See also

Further reading

Notes

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page x, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page vii, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 35, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page vii, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, Book dust jacket, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 18, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 42-43, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 58-60, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 66, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 69, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 70, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 82, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 88-89, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 94, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 115-116, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 127-128, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 131-132, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 141, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 143-144, 147, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 165, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 167, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 168, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 169, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 176, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 178-181, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 187, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 188-189, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 192-3, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 194, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 198, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 203, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 208, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 211, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 219, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 232-235, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 240-1, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 254-5, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 258-9, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 265, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 266, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 275, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 277, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 278, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 279, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 284, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 287, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 300, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 306, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 307, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 309, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 316, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 319, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 320-21, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 323-24, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 325, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 331, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 333, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 342, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 344, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 347, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 354, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 356-7, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 358-9, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 362, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 373, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 374-5, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 377, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 379, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 393, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 406-7, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, page 410, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr., The Imperial Presidency, pages 417-8, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. [ISBN 0-395-17713-8]