CoreCivic

|

Learn more about corporations VOTING to rewrite our laws. |

CoreCivic formerly called Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), incorporated in Maryland and headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee, is the largest owner of for-profit prisons and immigration detention facilities in the United States. The only larger operators of such facilities are “the federal government and three states,” according to CCA. [1] It is publicly traded in the United States (NYSE: CXW) and had approximately 15,400 employees in 2013.[2] In 2013, CCA was converted into a real estate investment trust (REIT), which will help the company avoid tens of millions of dollars in corporate taxes.[3][4] CCA's revenue in 2013 was nearly $1.7 billion, and it had profits of $300 million, 100 percent of which came from taxpayers via government contracts.[2]

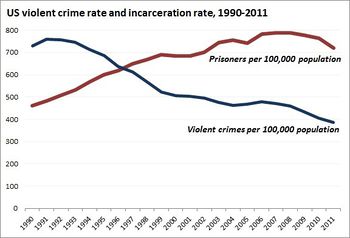

Since its founding in 1983, CoreCivic has profited from federal and state policies that have led to a dramatic rise in incarceration and detention in the United States -- a rise of 500 percent over the past thirty years.[5][6][7] As of 2011, around half of all prisoners in state facilities were there for nonviolent crimes, and half of inmates in federal prisons were serving time for drug-related offenses.[8]

Studies have shown that for many offenses, incarceration has little if any impact on public safety, and that time in prison actually increases a person's likelihood of committing more crimes.[9][10]

According to the Justice Policy Institute: "While private prison companies may try to present themselves as just meeting existing "demand" for prison beds and responding to current "market" conditions, in fact they have worked hard over the past decade to create markets for their product."[11]

Although it claims that it has not lobbied for bills that extend or increase sentences for prisoners, for nearly two decades CivcCore participated in and even led the task force of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) that pushed bills like so-called “truth-in-sentencing” and “three strikes” legislation as models for states to adopt across the nation. Civic Core and its hired lobbying firms have spent about $21.1 million lobbying Congress and federal agencies from 1998 to August 2014 on bills relating to immigration, detention, and private prisons.[12] CoreCivic has spent an untold sum lobbying for states to privatize or outsource incarceration responsibilities, and over that same period, it has steadily increased its share of both state and federal prisoners or detainees over the years, to 128,195 prisoners as of 2010.[13]

The company has become a multi-billion-dollar corporation that has been strongly criticized for many aspects of its operations, which amount to two primary critiques: (1) CoreCivic's lobbying and campaign donations have led to federal and state policies and government contracts that fatten its bottom line, often at the expense of the public interest; (2) CoreCivic’s profit-increasing strategies constitute a vicious cycle where lower wages and benefits for workers, high employee turnover, insufficient training, and chronic understaffing can lead to mistreatment of inmates, increased violence, security concerns, and riots. As discussed below, profit-focused measures that affect inmates, such as withholding medical care or inadequate nutrition, add to the volatility of the situation. This, in turn, has led to dangerous working conditions for correctional staff. CoreCivic's history also includes allegations of falsifying records, fraudulently billing Medicaid, violating labor laws, and all around "cutting-corners."

Contents

- 1 Profiting From More People Behind Bars

- 2 Ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council

- 3 Cost Cutting Leads to Violence, Abuse, and Death

- 4 CCA Cuts Costs at the Expense of its Workforce: Allegations of Federal Labor and Wage Law Violations and Employment Discrimination

- 5 CCA Cuts Costs, But Taxpayers Don't See the Savings

- 6 Investors

- 7 Political Activity

- 8 "Risk Factors" in SEC Filings

- 9 History

- 10 Personnel

- 11 Contact Information

- 12 Resources and Articles

PROFITS AND OWNERSHIP: CoreCivic, which is publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol CXW, took in nearly $1.7 billion in revenue in 2013, 100 percent of which came from taxpayers via government contracts. It had profits of $300 million in the same year--almost double the previous year's profits.[2] In early 2013, CoreCivic transformed itself into a real estate investment trust (REIT), a restructuring designed to reduce the payment of federal income taxes. In the first quarter of 2013, the firm realized a $137.7 million income tax benefit related to the company's recent conversion into a REIT.[14]

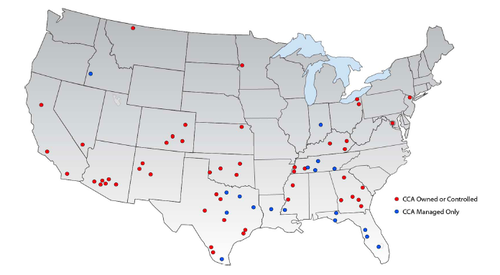

BUSINESS MODEL: CCA operates 66 correctional and detention facilities, 53 of which they own, with a total capacity of approximately 86,000 beds in 20 states and the District of Columbia.[2] According to its SEC filings, "v is the clear leader of private prisons, controlling approximately 44% of the private corrections and detention beds in the United States. CoreCivic provides housing and services under approximately 90 agreements with various federal, state, and local agencies."[1][15] The company also has a wholly-owned subsidiary, TransCor America, through which it profits from providing "prisoner transportation services."[1]

For-profit prison companies contract with federal and state governments to either take over management of a state-run facility or house people in a privately constructed prison; in at least one case, CoreCivic purchased a publicly-owned prison and converted it to private control and management. Private prisons generally charge a daily rate per person incarcerated to cover investment, operating costs, and turn a profit. This daily rate varies depending on location, bargaining leverage, stipulations in the contracts for occupancy guarantees, caps on medical care, population, and security level, but usually pays for correctional officers, support staff, food services, programmatic costs and partial medical care among other services."[11]

FOUNDING: CCA was founded in 1983 by Tom Beasley, Don Hutto, and Doctor Robert Crants (whose first name is "Doctor" but who is not a physician or PhD).

CCA’s first contract, in 1983, was with the Reagan Administration’s Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) (a federal agency that was subsequently reorganized to become part of the Department of Homeland Security and its enforcement operations were renamed ICE). That contract was to house detained immigrants in Texas. The following year, CCA obtained a contract to manage a juvenile detention facility in its home state of Tennessee, and two years later, CCA opened the “Shelby Training Center,” the first privately owned and operated juvenile detention center in the U.S. It also created the first privately owned women’s prison in New Mexico in 1989. (See below for information about allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination by women staff members, and prisoner abuse and sexual assault at CCA's women's prisons.)[16]

Profiting From More People Behind Bars

CCA's business model rests on incarceration. The more individuals locked up, the more CCA and its shareholders profit. Increases in CCA's earnings and stock prices have corresponded with America's incarceration boom -- and laws that criminalize a longer list of conduct and require that those convicted serve longer sentences are good for business.

According to the Justice Policy Institute: "Since private prison companies are in the business to make money, policies that maintain or increase incarceration boost their revenues; from a business perspective, the economic and social costs of mass incarceration are "externalities" that aren’t figured into their corporate bottom line."[11]

Indeed, the company has faced challenges in recent years as the public has slowly shifted away from a tough-on-crime model. CCA has acknowledged in its 10-K filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission that its profitability may be hurt by new developments in criminal justice such as “the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices, or through the decriminalization of certain activities.”[17]

Although CCA has denied lobbying for criminal justice or sentencing laws, CCA's own contracts requiring a guaranteed occupancy rate for its prisons has a similar impact: these bed guarantee clauses can encourage tough enforcement and sentencing policies, or, at a minimum, can help deter reform.

CCA's role in the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which has advanced harsh sentencing measures, has raised raised additional questions.

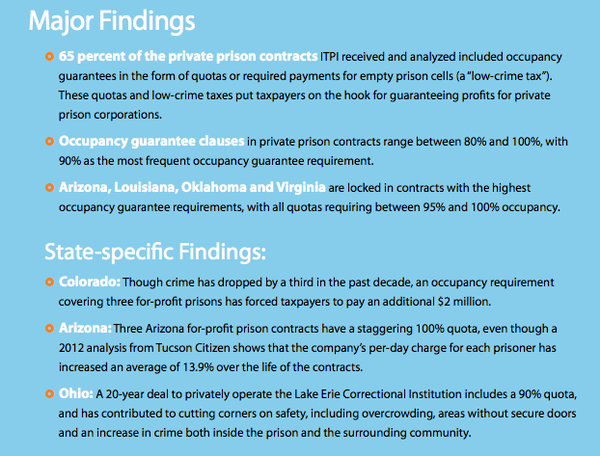

Occupancy Guarantees or Quotas in CCA Contracts Keep Prisons Full and Profits Up

In January 2012, CCA sent a $250 million proposal to prison officials in 48 states offering to purchase their facilities -- as long as the state promised to keep the facility ninety percent occupied over the duration of the 20 year-plus contract. Taxpayers would have to pay CCA for any unused beds if the occupancy rate dipped below ninety percent at any time. (This was an effort by CCA to duplicate its purchase in 2011 of the 1,798-bed Lake Erie Correctional Institution from the state of Ohio for $72.7 million, along with a ninety percent bed guarantee; as discussed below, the facility has had numerous operational problems since CCA took control.)

Roger Werholtz, former Kansas secretary of corrections, told USA Today that states may be tempted by the "quick infusion of cash," but it could warp public interest goals of reducing the prison population.

"My concern would be that our state would be obligated to maintain these (occupancy) rates and subtle pressure would be applied to make sentencing laws more severe with a clear intent to drive up the population," he said.[18]

No states took CCA up on its January 2012 offer, but many private prison operators have successfully inserted occupancy quota provisions into prison privatization contracts, according to a report by In The Public Interest (ITPI). Over half of the state and local level contracts analyzed by ITPI contained bed guarantee provisions; the occupancy requirements were between 80 and 100 percent, with many around 90 percent.[19]

In addition to warping a state's criminal justice goals, "these clauses can force corrections departments to pay thousands, sometimes millions, for unused beds. The private prison industry often claims that prison privatization saves states money. Numerous studies and audits have shown these claims of cost savings to be illusory, and bed occupancy requirements are one way that private prison companies lock in inflated costs after the contract is signed," ITPI wrote.[19]

Negotiating Occupancy Quotas After Contracts Are Signed

Many of the occupancy quota clauses were not in the original contract, but were instead added as an amendment after the initial contract was signed -- which CCA has identified as integral to revenue growth. In its 2010 Annual Report, for example, CCA explicitly cites “enhancing the terms of our existing contracts” as one of the approaches its uses to develop its business.

Colorado Prison Quotas

(Criminal--How Lockup Quotas and “Low-Crime Taxes” Guarantee Profits)

In some cases, CCA has inserted occupancy quotas outside of the contract process altogether. In Colorado, for example, CCA negotiated a provision in the 2013 budget guaranteeing that at least 3,300 prisoners would be housed in CCA's three Colorado facilities at an annual rate of $20,000 per inmate.[20] Over the past decade, Colorado's crime rate had dropped by a third, and five prisons closed between 2009 and 2013 -- propelling CCA to negotiate the deal behind closed doors, with no public hearings.

"The occupancy requirement not only ensured that CCA continued to receive a guaranteed level of revenue each month despite the decrease in inmates, but also had the effect of diverting inmates away from available public prison beds," ITPI wrote. "Colorado originally intended its private prisons to be used for overflow purposes, but the bed guarantee provisions allowed it to become the first priority for placement."[19]

Ohio Prison Quotas

In 2011, Ohio sold its Lake Erie Correctional Institution to CCA. It was the first-ever sale of a public prison to a private firm. The 20-year contract includes a 90 percent occupancy quota requiring that Ohio -- and its taxpayers -- keep 1,530 of the 1,700 available beds occupied. The situation is made worse by CCA squeezing an additional 300 beds into the facility after the purchase, violating minimum square footage-per-inmate requirements. "Notably, the head of Ohio's corrections department had served as a managing director of CCA," the ACLU has noted.[21]

After the sale, a report on the Lake Erie institution from the Correctional Institution Inspection Committee (CIIC) showed that violence, gang activity, and drug use was rampant in the facility. "Assaults, fights, disturbances and uses of force have all increased in comparison to prior years," the CIIC report found, echoing the findings of earlier reports on the facility.[22]

Additionally, both because of poor conditions within the prison and cost-cutting measures by CCA, there is extremely high turnover among staff, making conditions worse. Approximately one-fifth of personnel are leaving within the course of a year.[23]

(See this timeline from the ACLU documenting the declining conditions at the Lake Erie Correctional Institution after it was purchased by CCA).

Ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council

CCA is a member of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).

While CCA has been an ALEC member, ALEC pushed legislation to privatize prisons, and at the same time advanced harsh sentencing bills to put more people in prison for more time time, particularly "truth-in-sentencing" legislation calling for all violent offenders to serve 85 percent of their sentences before being eligible for release, and "three strikes you're out" bills requiring mandatory life imprisonment for a third felony conviction. These bills became law in a majority of states during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Laurie Shanblum, CCA's Senior Director of Partnership Development, was the corporate chair of the Public Safety and Elections Task Force during portions of the mid-to-late 1990s, and was listed as a member of the task force's Executive Committee circa July 2011.[24][25] Shanblum was also on that task force's Homeland Security Subcommittee during the same time period.[26]

| About ALEC |

|---|

ALEC is a corporate bill mill. It is not just a lobby or a front group; it is much more powerful than that. Through ALEC, corporations hand state legislators their wishlists to benefit their bottom line. Corporations fund almost all of ALEC's operations. They pay for a seat on ALEC task forces where corporate lobbyists and special interest reps vote with elected officials to approve “model” bills. Learn more at the Center for Media and Democracy's ALECexposed.org, and check out breaking news on our ExposedbyCMD.org site.

|

Connections to ALEC and Harsh Sentencing Laws, which Drove Up CCA's Profits

Reporting at In These Times in 2010, investigative journalist Beau Hodai wrote:

- "In the early '90s, the ALEC's Criminal Justice Task Force [later known as the Public Safety and Elections Task Force] was co-chaired by Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the country's largest private prison company. During those years, the National Rifle Association (NRA), another task force member (and the current task force co-chair), initiated a campaign to introduce two pieces of ALEC-inspired legislation at the state and federal level: the so-called "truth-in-sentencing" and "three-strikes-you're-out" laws. Truth-in-sentencing called for all violent offenders to serve 85 percent of their sentences before being eligible for release. Three strikes called for mandatory life imprisonment for a third felony conviction.

- The NRA campaign, dubbed "CrimeStrike," was seen by many as a reaction to the Clinton administration's efforts to pass gun control. CrimeStrike set forth the precept that "guns don't kill people, people kill people" and derided any legislator backing gun control as being "soft on crime." With memories of the Willie Horton disaster of the failed 1988 Michael Dukakis presidential campaign still on the minds of lawmakers, this accusation hit a nerve and elicited knee-jerk support of the laws by Democrats."[27]

An ALEC/NRA CrimeStrike report from 1994 can be viewed here; in addition to calling for tough sentencing laws, the report demands "the legal authority for the states and localities to privatize prisons, jails, and other detention facilities."

CCA was also involved with ALEC's "crime control" efforts. At a 1994 ALEC conference, for example, CCA's Robert Britton and Crime Strike's Steve Twist were part of a presentation titled "Campaign School on Crime" designed "to provide legislators with an agenda and plan to advance meaningful crime control this fall and during the coming legislative session." [28]

ALEC bills adopted and promoted during CCA's association with the group, which would potentially expand CCA's profits, include:

- 7D9 Shock Incarceration Act Exposed

- 7D10 Third Theft Felony Act Exposed

- 7D11 Truth in Sentencing Act Exposed

- 7F0 Criminal Justice Drug Testing Act Exposed

- 7F1 Drug Dealer Liability Act Exposed

- 7F2 Drug-Affected Infants Act Exposed

- 7F3 Drug-Free Housing Project Act Exposed

- 7F4 Drug-Free Post-Secondary Education Act Exposed

- 7F5 Drug-Free Schools Act Exposed

- 7F6 Drug-Free Workplace Act Exposed

- 7H2 Habitual Violent Offender Incarceration Act Exposed

- 7H3 Intensive Probation Act Exposed

- 7I0 Money Laundering Act Exposed

- 7J7 Defense of Free Market and Public Safety Resolution Exposed

- 7K3 Immigration Law Enforcement Act Exposed

- 7K4 Laser Safety Act Exposed

- 7K5 No Sanctuary Cities for Illegal Immigrants Act Exposed (SB1070)

- 7K6 Resolution Against Amnesty Exposed

- 7K7 Resolution in Opposition to the REAL ID Act Exposed

- 7K10 Resolution to Enforce Our Immigration Laws and Secure Our Border Exposed

- 7L0 Habitual Juvenile Offender Act Exposed

- 7L1 Juvenile Identification Act Exposed

- 7M4 Mandatory Sentencing for Repeated Felony Theft From a Retail Store Act Exposed

- 7N0 Housing Out-of-State Prisoners in a Private Prison Act Exposed

- 7N1 Inmate Labor Disclosure Act Exposed

- 7N2 Model State Bill Prohibiting Wireless Handsets in Prisons Exposed

- 7N3 Prevention of Illegal Payments to Inmates Incentive Act Exposed

- 7N4 Prison Industries Act Exposed

- 7N5 Resolution on Prison Expenditures Exposed

- 7N6 Targeted Contracting for Certain Correctional Facilities and Services Act Exposed

- Private Correctional Facilities Act

Case Study: Wisconsin "Truth-in-Sentencing"

An American Radio Works report from 2002 analyzing the connections between ALEC, harsh sentencing laws, and CCA discussed a case study in Wisconsin:- "In Wisconsin, a group of lawmakers led passage of truth-in-sentencing in 1998.

- 'Many of us, myself included, were part of ALEC,' says the bill's author, [then] Republican state representative Scott Walker.

- 'Clearly ALEC had proposed model legislation,' Walker recalls. 'And probably more important than just the model legislation, [ALEC] had actually put together reports and such that showed the benefits of truth-in-sentencing and showed the successes in other states. And those sorts of statistics were very helpful to us when we pushed it through, when we passed the final legislation.'

- But a former head of Wisconsin's prison system, Walter Dickey -- now a University of Wisconsin Law Professor -- says he finds it 'shocking' that lawmakers would write sentencing policy with help from ALEC, a group that gets funding and, supposedly, expertise, from a private prison corporation.

- 'I don't know that they know anything about sentencing,' Dickey says. 'They know how to build prisons, presumably, since that's the business they're in. They don't know anything about probation and parole. They don't know about the development of alternatives. They don't know about how public safety might be created and defended in communities in this state and other states.'"[30]

As a legislator, Walker also promoted prison privatization in the state (albeit unsuccessfully).[31]

The Wisconsin state legislature apparently recognized the folly of truth in sentencing and rolled back aspects of the law between 2001 and 2009. When Scott Walker became governor in 2011, however, he reversed this progress and pushed for legislation fully restoring the ALEC corporate-supported truth in sentencing, despite the costs to taxpayers and despite claiming Wisconsin was "broke." In early July 2011, Governor Walker's office released a statement supporting expanded use of prison labor, another idea promoted in ALEC bills. Some observers speculated that private prisons would be next.[32]

(See this graphic from American Radio Works explaining the CCA-ALEC-Wisconsin sentencing law connection.)

Connections to the ALEC/Arizona SB1070 Anti-Immigrant Law

In 2009, Arizona State Senator Russell Pearce (R-Mesa), the ALEC State Chair for Arizona, brought the No Sanctuary Cities for Illegal Immigrants Act" -- later to become known as "S.B. 1070" -- to ALEC for adoption as a "model" bill.At the time, CCA was an executive member of ALEC's Public Safety and Elections Task Force, as was Sen. Pearce.[27] Lobbyists for CCA and other private prison industries were in the room when the bill was adopted as a "model;" while CCA stood to profit from increased immigration enforcement and detention, it denies it had any role in crafting the bill.

A few months later, Pearce introduced the ALEC "No Sanctuary Cities for Illegal Immigrants Act" as Senate Bill 1070 (S.B. 1070), and it quickly passed the legislature and was signed into law by Governor Jan Brewer, an ALEC alumni.

30 of the bill’s 36 co-sponsors promptly received campaign contributions from the for-profit prison industry. A little over a week after Pearce introduced S.B. 1070, CCA enlisted Highground Consulting, one of the most influential lobbying firms in Phoenix, to represent its interests in the state.

In addition, Governor Jan Brewer's spokesperson had previously worked as CCA's chief lobbyist in Arizona during his time at the Policy Development Group. CCA also made other hiring decisions to increase its influence in Arizona prior to the bill's introduction. For example, Brad Regans, CCA "Vice President of State Partnership Relations," was formerly the director of fiscal policy in the Arizona House, and former Arizona Senator Dennis DeConcini was selected to be a member of the Board of Directors for CCA.[27]

(In 2012, much of S.B. 1070 was struck down by the Supreme Court in the case Arizona v. United States, 567 US ___ (2012)).[33]

Immigrant Detention Is CCA's New Profit Center

State prison populations have been declining in recent years, but federal numbers have increased -- thanks in no small part to a rise in immigration detention.[34][35] In 2012, CCA derived 30 percent of its revenue from federal contracts.[35] From 1970 to 2005, the number of people locked up in the US shot up by 700 percent, according to an ACLU report. Between 1990 and 2009, the number of prisoners behind private prison bars expanded significantly from 7,000 to 129,000 inmates, an increase of 1600 percent.[36]CCA, along with other private prison companies, were on the brink of financial collapse in the 1990s following widespread stories of escapes, inmate violence, and deplorable conditions in their facilities, not to mention declining crime rates, speculative prison building, and other factors. CCA's stock had lost 93 percent of its value in the year 2000. The company and the industry as a whole rebounded in the early 2000s, following a massive increase in the amount of illegal immigrant detentions in the wake of 9/11, which created a whole new market for its facilities. From 2001 to 2011, CCA revenue increased 88 percent, and they managed to receive at least $1 billion in revenue for each of the eight years from 2003 to 2011.[37]

The Huffington Post reports:

- "Because of punitive drug laws, drug offenders still make up more than 46 percent of the federal prison system, according to the Department of Justice. Immigrants are the third-highest category of offenders, at 11 percent. But this year, more than 60 percent of all federal criminal convictions have been for immigration-related crimes, federal data show."[35]

In the wake of September 11, 2001, the George W. Bush administration began a zero-tolerance policy known as "Operation Streamline," [38] arresting and detaining people at the border. No longer were immigrants deported relatively rapidly or put into a civil detention center. This led to a four-fold increase in immigration cases from the previous decade, as research from Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse showed in 2012. "This is the crime du jour," states Justice Strategies director Judith Greene. "It's the drug war all over again. It's what's driving the market in federal prisons."

This resulted in significant windfall for private companies such as CCA and GEO Group: $546 million for CCA came from federal contracts with the Bureau of Prisons and the U.S. Marshals Service in 2012.[39] $384 million was pocketed by GEO in 2012, 25 percent of its revenue from both agencies.[40]

Although for-profit prison companies like CCA and GEO Group have denied lobbying to influence immigration policy, the evidence suggests otherwise. For example, an analysis by the Associated Press in 2012 found that the three major private prison corporations -- CCA, the GEO Group, and another smaller company -- spent roughly $45 million over the past decade on campaign donations and lobbyists.[34] The private prison corporations specifically target Republican legislators over immigration "reform."[41] The companies' success in lobbying echoed their harnessing the zeitgeists of the preceding decades, from "Tough On Crime" in the 1980s and 1990s, and terrorism-induced blowback to immigration in the early 21st century.[42]

Hedging Bets and Investing in Correctional Alternatives

As state and federal authorities move away from incarceration-focused responses to crime, CCA has begun acquiring companies that offer "alternatives to incarceration."

In August of 2013, for example, CCA acquired "Correctional Alternatives, Inc," a company that focuses on community corrections and reentry programs, for $36 million.[43]

Cost Cutting Leads to Violence, Abuse, and Death

One of the most common critiques of private prisons is that the industry's goals of maximizing profits are at odds with the traditional goals of the criminal justice system, such as offender rehabilitation, reducing recidivism rates, increasing public safety, and lowering crime rates.In addition to making more profits when more people are behind bars, CCA's cost-cutting measures have led to an extensive record of inmate-on-inmate and guard-on-inmate (and vice-versa) violence which are many times a result of inadequate training, low pay and high turnover of corrections staff as well as chronic understaffing.

Further allegations of civil rights abuses and medical neglect have resulted in individual and class-action lawsuits brought against the company. For example, a spreadsheet of lawsuits complied by Private Corrections Working Group/Private Corrections Institute lists 575 lawsuits filed against CCA that were settled before trial. These suits range from employment discrimination to inmate abuse allegations and were filed between 1998 to 2008.[44]

Prisoner Abuse, Violence, Riots, and Escapes in CCA Facilities

According to numerous reports, incidence of violence is, on average, significantly higher in private prisons than in publicly-managed prisons.

For example, in 2011, the Private Corrections Institute (PCI) obtained data from the Tennessee Department of Correction (TODC) revealing that incident rates involving assaults and disturbances at CCA-run prisons were consistently higher than at publicly-operated prisons in Tennessee from January 2009 to June 2011.[45]

PCI Reports: "In terms of rates per 1,000 prisoner population, the privately-operated prisons had notably higher incident rates. For 2009, the average rate of incidents at the 11 state-run prisons was 13.92 per 1,000 population, while the average rate at the three CCA facilities was 18.68 -- 34% higher than at TDOC prisons. The 2010 average rate of incidents at TDOC facilities was 14.51 per 1,000 population and the average rate at the CCA prisons was 18.68 -- 28.7% higher than at the state operated facilities. During the first six months of 2011, the average rate of incidents at TDOC prisons was 15.0 per 1,000 population while the average rate at the CCA facilities was 17.44 -- 16.2% higher than at the TDOC prisons."[45]

Many of these problems can be attributed to high employee turnover, inadequate training for officers, under-staffing, and miserable conditions experienced by the inmate population.[46]

Below are just a few examples of lawsuits and complaints alleging prisoner abuse and sexual assault, the withholding of medical care resulting in death, and negligently allowing violence, riots, and escapes in CCA-run facilities:

Violence, Riots, and Escapes Resulting in Injury or Death

- CCA-Run Idaho "Gladiator School" : The CCA-operated Idaho Correctional Center (ICC) had experienced egregious levels of violence, earning itself the nickname the "Gladiator School." The Idaho Department of Correction determined in a 2008 study that the ICC had “four times more prisoner-on prisoner assaults than Idaho’s other seven publicly-operated prisons combined.” CCA employees were alleged to have been complicit in the violence, using violence as a "management tool" and failing to protect vulnerable prisoners from predatory inmates.[47]

- A complaint filed by the ACLU alleges, "ICC is an extraordinarily violent prison. It is known in Idaho as 'Gladiator School' for a reason. More violence occurs at ICC than at Idaho's eight other prisons combined, and the unnecessary carnage and suffering that has resulted is shameful and inexcusable. ICC not only condones prisoner violence, the entrenched culture of ICC promotes, facilitates, and encourages it. Indeed, ICC staff cruelly use prisoner violence as a management tool." Additionally, videos released to the press showing inmate-on-inmate violence prompted an FBI investigation into the CCA-run facility.[48]

- Court documents unsealed in August 2013 showed that the violence was partially attributable to CCA understaffing the facility. Even after a settlement requiring that they hire more guards, CCA falsified at least 4,800 staff hours, filing reports with the state showing that security posts were filled when they were actually vacant; the ACLU estimates that the total could be as high as 20,000 falsified staff hours.[49] The Idaho Department of Corrections is investigating how many hours have been understaffed in recent years, and the Idaho State Police are investigating whether CCA committed any crimes by making the false statements. [50]

- The lawsuit was settled in September 2011, but approximately one year later, the ACLU said CCA was violating the settlement, which required staffing and safety changes at the prison.[51] The Associated Press reported in November 2012: "The separate lawsuit filed by a group of eight inmates late last week echoed allegations made in the ACLU case, with the inmates saying CCA is working with a few powerful prison gangs to control the facility. The eight inmates also allege that CCA has violated the settlement with the ACLU by engaging in a ‘persistent pattern of misconduct.'"[52]

- In September 2013, a federal court found CCA in contempt of court for failing to comply with the settlement agreement and lying about its staffing levels. U.S. District Judge David Carter issued a scathing 24-page ruling warning that he would make the fines as high as necessary to force compliance. [50]

- "If a prospective fine leads to $2.4 million in penalties, CCA has no one to blame but itself," Carter wrote.

- According to Judge Carter's order, any mandatory security post left unstaffed for more than 12 hours in a month will bring fines of $100 an hour, with the judge warning he would raise the fine to $500 an hour or higher if the situation does not change.

- 24-Year-Old CCA Corrections Officer Dies in Missouri Prison Riot: In May 2013, the family of slain officer Catlin Carithers filed a lawsuit alleging that Officer Carithers was on a "hit list" and that CCA was negligent in preventing his death.[55] The complaint alleges that "the facility was short staffed and underequipped [sic], and the inadequate staffing and treatment of the inmates created dangerous working conditions for the corrections officers working there." The complaint further alleges that CCA knew this and "did not increase staff at the facility, modify the treatment of the inmates, or resolve the dangerous atmosphere experienced by the correction officers."

- CCA Settles Prison Riot Suit in Colorado for $600,000: Hundreds of prisoners alleged in a lawsuit that CCA instigated and mishandled a prison riot in 2004, used excessive force during and after the riot, and continued to mistreat prisoners afterwards.[56]

- "The plaintiffs attorneys say that frightened inmates had warned CCA guards for days that inmates transferred to the Colorado prison from Washington state were planning a riot because they were angry about being moved far away from their families." Additionally, a report from the Colorado Department of Corrections later showed that the CCA facility was plagued by high staff turnover and was slow to fix problems pointed out by inspectors.[57]

- In April 2013, CCA settled the claims of 193 inmates for $600,000.

- Jury Finds CCA Negligent and Awards Woman $500,000 After Escaped CCA Prisoner in Tennessee Took Her Hostage: "Rosetta Willis was taken hostage by a prisoner who escaped from the custody of two Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) guards at the Madison County, Tenn. General Hospital in August 1999. She filed a negligence suit against CCA seeking damages for medical bills, lost earnings, and severe emotional and psychological injury. In 2003, a jury found CCA liable and awarded Willis $500,000 in damages."[58]

- Three Individuals Sue CCA Subsidiary, TransCor America, for Alleged Mistreatment During Transport: According to the complaint filed in 2003, the three individuals were being transported to and from various jails by TransCor America, LLC. The Plaintiffs alleged that they "were denied bathroom breaks, they were denied proper food and drink, they were deprived of medication, and they were ultimately kidnapped, in Clarksburg, West Virginia, by another prisoner, due to the negligence of the CCA employees who were driving the van." The lawsuit was settled in 2005 for an undisclosed amount.[59]

- Inmate Sues CCA for Negligence Resulting in Physical Assault in Oklahoma Facility : According to the complaint, Brandon McKnight was attacked and beaten by a fellow inmate at the CCA-managed Tulsa County jail. McKnight alleged that CCA was negligent when it placed him and his assailant in the same holding cell. The complaint also alleged that, prior to his commitment to the facility, "defendants [CCA] failed to adequately train the jail staff to properly supervise the Jail inmates. Said defendants also failed to have an adequate number of staff, failed to utilize adequate methods, procedures and equipment for preventing or reducing the risk of injury to inmates . . ."[60]

- In December 2002, CCA settled the lawsuit for an undisclosed amount. (In his complaint, McKnight asked for $75,000 in damages, plus fees, costs, and interest.) [60]

Prisoner Abuse and Sexual Assault

- ACLU Alleges Rampant Sexual Abuse of Immigrant Detainees by Officers and Employees at CCA-Run ICE Facility in Texas: In 2011, "The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of immigrant women who alleged they were sexually assaulted while in the custody of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in Texas. The alleged attacks involved detainees who were being transported from the T. Don Hutto Family Residential Center in Taylor, Texas. The lawsuit names as defendants three ICE officials; Williamson County, Texas; Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the manager of the Hutto facility; the former facility administrator; and a guard."[61]

- The lawsuit alleges that the officer sexually assaulted each of the women and is known to have assaulted at least six others between October 19, 2009, and May 7, 2010, when he transported them from the Hutto facility to either the Airport or the Greyhound Bus Station after they were released from detention. It further alleges that this officer had the opportunity to assault these women because CCA repeatedly violated its Intergovernmental Service Contract with the County by allowing male officers to transport female detainees without the presence of another officer, much less a female officer. The lawsuit states that the "victimized women, all of whom had fled their home countries to escape extreme violence, and who were agonized and vulnerable from their journeys and from the disgusting conditions they experienced in holding cells and detention centers in the United States, were of necessity severely traumatized by these assaults," and "[t]he Defendants, both individually and collectively, were directly responsible for the assaults and the resulting trauma in that they failed to implement and enforce the contracts, policies, and standards clearly and obviously designed to protect these women and others like them."[62] According to the ACLU, since 2007, there have been 56 allegations of sexual abuse of immigrant detainees in Texas alone.[63]

- (See also the ACLU press release and ACLU - Sexual Abuse in Immigration Detention.)

- CCA Workers Charged With Sexual Abuse at CCA-Owned Otter Creek Correctional Center in Kentucky: At least six CCA workers were charged in 2010 with sexually abusing as many as 16 female inmates at the Otter Creek Correctional Center in Kentucky.[64][65]

- The New York Times reported, "pay at the [CCA-run] Otter Creek prison is low, even by local standards. A federal prison in Kentucky pays workers with no experience at least $18 an hour, nearby state-run prisons pay $11.22 and Otter Creek pays $8.25. Mr. Friedmann [associate editor of Prison Legal News] said lower wages at private prisons lead to higher employee turnover and less experienced staff."[65]

- The facility housed female inmates from Kentucky and Hawaii. After the sexual abuse allegations became public, Hawaii decided to bring the prisoners back to the islands.[65] The New York Times reported that the Governor of Hawaii, "Linda Lingle, a Republican, said that bringing prisoners home would cost hundreds of millions of dollars that the state did not have, but that she was willing to do so because of the security concerns." Hawaii initially sent inmates to the Kentucky prison to try saving money.[65]

- 81 percent of the facility's workers were men and only 19 percent were women -- the opposite of what the ratio should be, according to some prison officials. [65] The facility initially housed men, but became a women's prison in 2005, after CCA threatened to close the facility because it claimed there was too much vacant space.[64]

- In 2010, after the sexual abuse scandal was uncovered, Kentucky removed all female inmates from the Otter Creek facility. In 2013, the prison closed[66]

- Federal Jury Awards Juvenile $125,000 in Actual Damages and $3 Million in Punitive Damages for Abuse of 14 Year Old Boy by CCA Guards in South Carolina: "A lawsuit was filed on behalf of William P., a 14-year-old boy who claimed he was physically abused by guards at a CCA-managed juvenile detention facility in Richland, South Carolina. In December 2000, a federal jury awarded him $125,000 in actual damages and $3 million in punitive damages."[67]

- Female Prisoner Sues for Sexual Assault by Guard from CCA Subsidiary TransCor America: The ACLU filed a lawsuit against CCA's TransCor America subsidiary on behalf of a female prisoner who claimed she was sexually assaulted by a TransCor guard while being transported from Texas to Colorado. In April 2002, TransCor settled the lawsuit for an undisclosed amount.[68]

- Vermont Man Housed in a CCA-Operated Kentucky Prison Sues for Sexual Assault by Prison Guard: In 2005, CCA settled a case with a Vermont man who was housed in a Kentucky prison and brought suit alleging he was sexually assaulted by a guard. The guard was arrested and charged with sexual abuse and official misconduct.[69]

- Prisoner Abuse Class Action Lawsuit Over CCA's Ohio Facility Settled for $1.65 Million Plus $756,000 in Fees and Expenses: "Washington, D.C. inmates who were transferred to the CCA-managed Northeast Ohio Correctional Center filed a lawsuit claiming they were physically abused, not adequately protected and denied adequate medical care at the facility. In March 1999, CCA agreed to pay $1.65 million plus $756,000 in fees and expenses to settle the lawsuit."[70]

Deaths Resulting from Withholding Medical Care

- CCA-Managed Dawson State Jail in Texas Closes; Several Deaths at the Facility Due to Inadequate Medical Care: Dawson State Jail in Dallas, Texas is a low-security facility for people convicted of non-violent crimes. In response to several deaths at the facility, organizations like Grassroots Leadership and The Sentencing Project successfully advocated for the closure of the facility.[71] The organizations reported that the facility had experienced seven deaths since 2004, deaths that the groups say might have been prevented if those inmates had received proper medical care and attention from CCA staff.[72]

- The Dallas/Fort Worth CBS affiliate ran a four-part investigative report on the deaths and allegations of medical negligence at the jail. They reported that one thirty-year-old woman who was serving an 18-month sentence for drug possession died of pneumonia just six weeks before she was scheduled to be released.[73] Another woman died from pneumonia complications while she was serving a six-month sentence for drug possession.[74] Also, in 2010, a forty-five-year-old woman died while serving a one-year sentence for drug possession. The lawsuit filed by her family alleges that she was taken off her prescribed insulin injections and given cheaper oral insulin, resulting in diabetic comas. She continued to be denied insulin injections and died from complications from diabetes.[75][76]

- Inmate Dies After Being Denied Medication (to Save $35) Shortly Before He Was Scheduled to Be Released – A mother filed a lawsuit against CCA for her son's death at the CCA-run Kit Carson Correctional Center in Colorado. He suffered from a hereditary condition that caused his breathing passages to swell, and he allegedly died because staff at the CCA-managed facility refused to fill his prescription shortly before he was scheduled to be released. According to the complaint, CCA staff "did not obtain Winstrol [the medically necessary medication] for Mr. Buller because it could be obtained only in 30-day lots. Since Mr. Buller was scheduled to be released on or about May 2, 2001, CCA did not want to pay for a 30-day supply of the medication and CCA did not wish to incur the additional cost of approximately $35 for the Winstrol they would have had to order when Mr. Buller was only going to be at the facility for another ten days. Cost-cutting in the medical department had become a major concern for CCA." On the day Mr. Buller died, he tried to call for help from his cell, but as much as 30-45 minutes passed before CCA staff arrived to help. The complaint also alleges that "unit staff had the practice of turning on the intercom in an empty cell in order to cut off calls from inmates in occupied cells, thereby preventing inmates in occupied cells from ‘bothering' unit staff with calls." The lawsuit was settled out of court in 2004.[77]

- Quadriplegic Man Dies while Incarcerated at CCA-Managed Jail Five Days into a 10-Day Sentence: Twenty-seven-year-old Jonathan Magbie, who was paralyzed from the neck down when a drunk driver ran him over at age four, was sentenced to 10 days in jail for marijuana possession (his first offense).[78] He was placed in the Correctional Treatment Facility, a jail annex operated by CCA. [79] Magbie used a ventilator at night to sleep, which is common for quadriplegics to insure adequate oxygen intake. However, because of inadequate care and oversight at the CCA-managed facility and a corrections hospital, he was without his ventilator for five consecutive days, and died from lack of oxygen.[80][81]

CCA Cuts Costs at the Expense of its Workforce: Allegations of Federal Labor and Wage Law Violations and Employment Discrimination

The "cost savings" claimed by the for-profit prison industry is generally achieved at the expense of its workforce, by slashing wages and benefits for correctional staff. In fact, CCA boasts in its SEC filings that its business model helps state governments by "allowing them to avoid long-term pension obligations for their employees."[1] There is also evidence that the CCA has engaged in chronic under-staffing, falsified staffing records, and violated the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) by refusing to pay overtime.

For example, when CCA ran the Otter Creek prison in Kentucky (the state ended its contract in 2012),[82] the pay there was extremely low, even by local standards. In 2009, the government-run federal prison in Kentucky paid workers with no experience at least $18 an hour, and nearby state-run prisons paid $11.22, while the CCA-run Otter Creek paid only $8.25.[65] Also in 2009, it was reported that in Arizona, CCA paid correctional officers only $10 to $12 an hour while correctional officers in Arizona state prisons earned $18 to $20 an hour.[83]

Below are just a few examples of lawsuits alleging CCA's failure to pay employees overtime or pay for hours worked in general, as well as allegations of sexual harassment, discrimination, and anti-union activity.

Fair Labor Standards Act Violations

In order to keep profits up and costs down, CCA has allegedly engaged in a pattern of requiring non-exempt employees (employees who must be paid overtime for work over 40 hours in any week) to work off-the-clock, thereby denying them pay for work performed and overtime pay in violation of the FLSA. The company settled a suit in 2009, but may not have learned its lesson, because another suit was filed in 2012 alleging similar violations.

- CCA Settles Class Action Lawsuit in 2009 for $7 Million Dollars for Fair Labor Standards Act Violations: In 2008, corrections officers who had worked at CCA facilities across the country filed a class action lawsuit alleging rampant, company-wide FLSA violations. The complaint alleged that CCA did not pay employees for work they performed before or after their scheduled shifts and denied them overtime pay.

- CCA settled the case, agreeing to pay out up to $7 million in back pay and attorneys' fees for more than 30,000 CCA employees.[84][85]

- In 2012, Corrections Officers in Kentucky Sue CCA for FLSA Violations: Six corrections officers who worked at the CCA-operated Marion Adjustment Center in Kentucky filed a class action lawsuit against the company in 2012 for allegedly requiring work "off the clock" and failing to pay overtime.[86]

- Subsequently, Kentucky decided not to renew its contract with CCA for Marion Adjustment Center. This was the last CCA-operated prison in Kentucky after the state pulled out of Lee Adjustment Center in 2010 and Otter Creek Correctional Center in 2012.[87]

Allegations of Sexual Harassment and Discrimination

CCA has a record of alleged racial and gender discrimination, sexual harassment, and allegations that the company maintains a male-dominated workforce.

- CCA Pays $1.3 Million in 2009 to Settle Sexual Harassment and Retaliation Claims for Class of Women: In 2008, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) filed a complaint against CCA alleging that female staff members were subjected to sexual abuse, rape, and demands for sexual favors by their superiors at the CCA-owned Crowley County Correctional Facility in Colorado. According to a U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission press release:

- "Among the allegations in the court record are the following: A female officer made a complaint of sexual harassment against a male coworker, and was then placed in an isolated location, where she was raped by the man about whom she had complained. The Chief of Security forced a female corrections officer to have intercourse with him, which she did in order to keep her job. After that Chief of Security resigned, his replacement was the subject of numerous written complaints of sexual harassment, including complaints that he regularly commented on female employee’s bodies, and touched female officers inappropriately."[88]

- CCA settled in 2009 for $1.3 million.[88]

- CCA Agrees to Pay More Than $152,000 in Back Wages to 96 Women Denied Employment: In 2002, a U.S. Department of Labor audit showed that at least 96 female applicants at a CCA facility in Oklahoma -- who were equally or better qualified than men who were hired -- were rejected. The company agreed to pay $152,000 in back wages to the 96 women denied employment and offered jobs to 19 of the rejected female applicants.[89]

- Six Employees Sue for Racial Discrimination: Six former nurses at the CCA-run Marion County, Indiana jail filed a lawsuit in 2008 alleging a racially hostile work environment and claiming they were retaliated against for trying to report unsafe working conditions and other problems at the jail.[90]

National Labor Relations Act Violations and Anti-Union Activities

There is evidence that CCA has engaged in anti-union activities and committed Unfair Labor Practices (ULP) in violation of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). In 2006, the NLRB issued a decision finding that CCA interfered with protected concerted activity in violation of the NLRA by initiating a drive to decertify the union (International Union, Security, Police and Fire Professionals of North America (SPFPA)) and then coercing and threatening its employees to support the decertification drive. The board also upheld the finding that the company violated the NLRA by unlawfully transferring an officer to a less desirable position and unlawfully discharging another officer because of those individuals' union activities.[91] Also, in 2010, the NLRB reversed an earlier decision holding that CCA unlawfully discharged an employee in retaliation for protected union activity in violation of the NLRA.[92]

CCA Cuts Costs, But Taxpayers Don't See the Savings

According to the ACLU:

- "While supporters of privatization tout the idea that governments can save money through private facilities, the evidence for supposed cost savings is mixed at best. As state governments across the nation confront deep fiscal deficits, the assertion that private prisons demonstrably reduce the costs of incarceration can be dangerous and irresponsible.

- Such claims may lure states into building private prisons or privatizing existing ones rather than reducing incarceration rates and limiting corrections spending through serious criminal justice reform."[21]

Instances of Government Fraud and Tax Evasion

In other attempts to cut costs, CCA has been caught falsifying staffing records, engaging in Medicaid fraud, and creatively dodging taxes.

- CCA Employees in Idaho Falsify Staffing Records: On top of the many problems at the CCA-run Idaho Correctional Center known as the "Gladiator School" (violence, misconduct by guards, FBI and state police investigations), the company admitted that its employees had falsified nearly 4,800 hours of staffing records. CCA charged the state for thousands of staffing hours where security positions were actually vacant. The company placed the blame on its employees, stating, "We will take appropriate disciplinary action with the involved personnel, and we will work to enhance the staffing, training and record keeping processes at the facility."[93] However, a separate lawsuit filed in November 2012 alleges that the company falsified staff logs to hide chronic understaffing. This understaffing reportedly contributed to the unsafe conditions in the facility.[52]

- CCA Settles Charges of Medicaid Fraud in Florida: The Attorney General's Medicaid Fraud Control Unit in Florida found that, between January 2000 and May 2004, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) submitted fraudulent claims to the State of Florida Medicaid program in violation of the Florida False Claims Act. "The AG found that CCA, which provides health care services to inmates at facilities throughout Florida, improperly billed Medicaid for outside medical services provided to inmates. Pursuant to a civil settlement agreement with the state, CCA paid $298,115, which covered the improper Medicaid claims, the cost of the state’s investigation and a penalty."[94]

- CCA Pays $54 million to Settle 1997 IRS Audit:"In October 2002 CCA entered into a settlement agreement with the Internal Revenue Service in connection with the IRS’s audit of a 1997 federal income tax return filed by CCA’s corporate predecessor. Under the terms of the settlement, CCA paid approximately $54 million."[95]

Tax Avoidance

CCA transformed itself into a real estate investment trust (REIT) in 2013. "Designed to reduce the payment of corporate federal income taxes, REITs are a special tax designation for companies that focus on real estate holdings. CCA was able to make the successful claim to the Internal Revenue Service that the money they collect from government entities for holding prisoners is essentially the same as rent collection," explains a report from Grassroots Leadership.[3]

CCA's Chief Executive Damon T. Hininger said, "The good news about this is that we are going to be able to enjoy a full year of tax savings for 2013."[96] In the first quarter of 2013, the firm realized a $137.7 million income tax benefit related to the company's recent conversion into a REIT.[97]

Grassroots Leadership notes that, "at a time of drastic budget cuts throughout the public sector, CCA expects to make $70 million savings in tax payments for 2013 due to its REIT status."[98]

CCA had tried an REIT in the past, with "disastrous results." As Prison Legal News explains: "CCA formed Prison Realty Trust and a separate operating company, but due to various factors, including poor management decisions, the REIT defaulted on its debt and the company's stock dropped to under $1.00 a share, putting it at risk of being delisted from the New York Stock Exchange. CCA subsequently reversed its REIT conversion, and faced shareholder lawsuits that alleged various corporate officers and directors had concealed information and made false and misleading statements. The suits were eventually settled for approximately $104 million in stock and cash."[99]

Separately, in New Mexico in 2013, CCA sought a tax exemption from state, city, and local governments for payments it receives from the federal government for federal inmates held in facilities inside New Mexico; CCA eventually negotiated an exemption only from state taxes, while agreeing to taxes on the local level.[100][101]

States End Relationships with CCA

- Kentucky: Kentucky had housed prisoners in private prisons for approximately 30 years, including three CCA-run facilities, but decided not to renew its last contract with CCA in 2013.[102][103]

- Hawaii: After two lawsuits for inmate deaths and allegations of prisoner abuse, Hawaii stated its intention to bring prisoners back to the islands,[104] but in 2011, the state signed a new three-year deal with CCA in Arizona.[105][106] However, the contract was signed as Governor Neil Abercrombie's administration was reportedly making plans to end the state's longstanding policy of imprisoning Hawaiian inmates in out-of-state facilities.[107][108]

- In 2009, Hawaii had decided to bring female prisoners back from a CCA prison in Kentucky over sexual abuse charges.[65]

- Idaho: After lawsuits, violence, and falsifying records, Idaho ended its contract with CCA for the operation of Idaho Correctional Center (ICC).[53]

- Texas: In 2013, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice announced that two CCA-operated facilities would close: Dawson State Jail and Mineral Wells Pre-Parole Transfer Facility. Grassroots Leadership, along with its ally organizations, had advocated for the closure of the Dawson State Jail after the deaths of three incarcerated women and the death of a baby who was born to a woman at the jail with no medical personnel on site.[109] However, CCA still has 10 other facilities in Texas.[110]

- Mississippi: In May 2013, CCA lost its contract to operate the 1,000-bed Wilkinson County Correctional Facility. One month earlier, a riot at the facility resulted in the death of one 21-year-old prisoner, and many others were injured; it was the second riot in a year at the Wilkinson facility.[53] A year prior, at a different CCA-owned federal prison in Mississippi, a riot took the life of a 24-year-old guard.[111]

- Ohio: After 18 months of what the ACLU described as "dirty conditions, rampant drug use, and staggering increases in violence" at the CCA-owned Lake Erie Correctional Institution, the ACLU organization accelerated its push for Ohio to end its contract with CCA, but the facility remained open as of September 2013.[112][113]

- The ACLU has published a timeline of the continual issues experienced since the opening of the Lake Erie Correctional Institution.

Investors

According to Nasdaq, major investors in CCA include: Vanguard Group, Barclays Global Investors, BlackRock, Bank of New York Mellon, Credit Suisse AG, Morgan Stanley, and more.[114]

Damon T. Hininger, CEO of CCA, is a major stockholder with over 150,000 shares.[115] For more on investors, see Ray Downs, "Who is getting rich off the Prison Industrial Complex?," Vice, June 2013.

Political Activity

Lobbying

"Since private prisons make money from putting people behind bars, their lobbying efforts focus on bills that affect incarceration and law enforcement,such as appropriations for corrections and detention," the Justice Policy Institute notes. "Knowing that private prison companies bring in revenue from holding people in prison, it is likely that their lobbying efforts contribute to promoting the current approach to incarceration, and decrease the impetus for reform."[11]

CCA and its hired lobbying firms have spent about $21.1 million lobbying Congress and federal agencies from 1998 to August 2014, according to the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP).[12]

At the state level, the company has hired 272 lobbyists in 37 states from 2003 to 2012, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics.[116]

While additional firms have been used previously, from 2010 to 2013, CCA exclusively hired three outside lobbying firms for its federal lobbying, in addition to their in-house lobbyists. These firms include: McBee Strategic Consulting, Mehlman Vogel Castagnetti Inc., and Akin Gump et al. During this time (as well as in 2008 and 2009), the company's total federal lobbying expenses were around $1 million per year. This was a decline from the years 2004 to 2007, when lobbying expenditures were between $1.9 and $3.4 million per year.[12]

Although 2004 and 2005 were the two years of highest lobbying expenses, 2007 was the third largest spending year, largely because of the seven bills CCA lobbied for or against that year. The bill with the most reports, H.R. 1889, known as the "Private Prison Information Act of 2007," would have required private prisons to be subject to FOIA requests just as federal prisons and correctional facilities are. CCA vehemently opposed the bill. That and all similar bills have either died in or before subcommittee hearings, according to for-profit prison scholar Christopher Petrella.[117] CCA and its hired firms also lobbied heavily against another bill to end the use of private prisons for incarcerating inmates, H.R. 1890 or the "Public Safety Act."[118]

In the first half of 2014, CCA and its hired firms spent $530,000 on lobbying at the federal level, employing 25 lobbyists, 80 percent of whom have "revolving door" connections.[12]

Beyond bills directly impacting the private prison system, CCA has a possible stake in possible immigration reform, when new pathways to citizenship could disrupt the number of people detained in private prisons for their immigration status. A CCA spokesperson denied the company's involvement in immigration reform to The Nation in February 2013,[34] but lobbying reports show its efforts regarding border security bills in 2007-2008, such as the Border Security Act, and appropriations bills for the Department of Homeland Security. In 2014, CCA reported lobbying on bills related to funding for Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement.[119]

The Nation wrote of CCA's likely interests regarding immigration reform:

- "On the one hand, a pathway to citizenship and legal reforms sought by advocates could reduce the number of immigrants detained by CCA and its competitors in the private prison industry. 'Private prison corporations have an enormous stake in immigration reform,' says Bob Libal, a prison reform advocate with Grassroots Leadership. 'A reform that provides a timely pathway to citizenship without further criminalizing migration would be a huge hit to the industry,' he says."[34]

Grassroots Leadership also discussed the actions of CCA's in-house lobbyists on the Department of Homeland Security appropriations bills:[120]

- "Bart Velhulst, Jeremy Wiley, and Kelli Cheever, CCA's in-house lobbyists, were paid $1,070,000 in 2011 and $980,000 in 2012. They lobbied on the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Bill, particularly on provisions related to ICE detention; as well as the House of Representatives and the Senate on homeland security issues related to the private prison industry."[120]

At least as recently as 2010, CCA was a member of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which has not only promoted model legislation to privatize prisons, but also to put more people in prison through harsh sentencing laws and state-based anti-immigrant legislation.[121] Read more in the "Ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council" section.

Political Contributions

State Spending

CCA and its employees contributed $2.2 million in 28 states from 2003 to 2012, with contributions concentrated in California, Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Idaho, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics.[122]

Federal Spending

In addition to its extensive federal lobbying efforts, CCA has a PAC to disburse donations to federal candidates. From 2002 to July 2014, the CCA PAC contributed $1.67 million to various federal candidates, according to CRP. The majority of CCA's contributions have generally gone to Republican candidates, though Democratic candidates have received over $100,000 from CCA since 2002.[123]

In 2012, the company's Political Action Committee spent $305,957, with 86 percent of the PAC's contributions in federal races going to Republican candidates, according to CRP.[124]

In 2012, a landmark year for extraordinary amounts of campaign money, the PAC's largest contribution went to Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), a longtime advocate of the private sector.[125]

Despite the extraordinary levels of election dollars spent in 2012, the PAC's largest contributions occurred during the 2006 elections, with its largest donation being to Sen. Mike DeWine (R-OH), an incumbent who struggled against fellow GOP challengers when DeWine tried to dub himself as an "independent."[126] In 2004, DeWine had helped CCA acquire a federal contract to operate a prison in Youngstown, Ohio -- a facility which had been closed down in 1997 after dangerous conditions, including 20 stabbings and 2 murders, came to light.[127]

Many political contributions from 2002 onward from the PAC, or from CCA individuals, have largely gone to candidates from Tennessee, Texas, Ohio, and Georgia, according to CRP.[128]

CCA says its political contributions are an essential way for them to get involved in the political process and assert their agenda:[129]

- "At CCA, we believe that participation process is an important and appropriate part of our partnership relations efforts. We must education federal, state, and local officials on the benefits of partnership corrections, CCA's ability to assist them in meeting their corrections needs and our track record of success."

According to CRP, the top recipients of contributions from CCA in 2014 (as of August) were:[130]

House

- Chuck Fleischmann (R-TN), $5,000

- Diane Black (R-TN), $3,750

- John Culberson (R-TX), $3,000

- Tim Ryan (D-OH), $3,000

- John Carter (R-TX), $2,500

- Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), $2,500

Senate

- Lamar Alexander (R-TN), $10,000

- John Cornyn (R-TX), $5,000

- Mike Crapo (R-ID), $5,000

- John Hoeven (R-ND), $3,000

- Sherrod Brown (D-OH), $2,500

- Rob Portman (R-OH), $2,500

- Mark Pryor (R-AR), $2,500

Political Connections

CCA has had a close relationship with government officials from its inception: CCA-co-founder Tom Beasley was a former government official in Tennessee and Don Hutto headed prison systems in Arkansas and Virginia. Several of CCA's board members as of August 2014 previously served in state and federal government positions: John D. Ferguson served as Commissioner of Finance and Administration for the state of Tennessee. Donna Alvarado holds several appointments in Ohio government related to higher education and economic policy. Thurgood Marshall, Jr. was a Cabinet Secretary under President Bill Clinton.[131]

According to the Justice Policy Institute, other examples include:[11]

- "[Maine] Governor Paul LePage appointed former CCA Warden Joe Ponte as the Commissioner of the Maine Department of Corrections. While Maine currently does not have any private prisons, according to news reports, CCA has been in discussions with the town of Milo for the past 3 years over the possibility of building a $150 million facility. The appointment of Ponte and the $25,000 in campaign contributions LePage received from CCA raise concerns of increased access for CCA to open private prisons in Maine."[11]

- "After serving 18 years in the U.S. House of Representatives John Kasich retired in 2000 and took a managing director position in Ohio with Lehman Brothers. Lehman Brothers has a long standing history with private prison companies, spending most of the late 1990s and 2000s before their collapse underwriting bonds and managing credit for both CCA and Cornell. After winning the governorship of Ohio in 2010, Kasich laid out his plans for privatizing state prison operations along with appointing a former CCA employee to head the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction. Rounding out Kasich’s connections to CCA is his close friend and former Congressional chief of staff whose lobbying firm was hired to represent CCA in January 2011."[11]

- "In 2007, President George W. Bush nominated CCA's general counsel, Gustavus Puryear IV, to a lifetime appointment on the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee. Alex Friedmann, currently of Prison Legal News, organized a campaign to prevent his appointment. Beyond the concern that general counsel of CCA would be serving as judge in a district where CCA Headquarters is also located, Puryear did not have the qualifications to hold the position. Among the most prominent issues, Puryear lacked litigation and trial experience, received a comparatively low rating in the American Bar Association‟s review of judicial nominees, had close, personal and professional ties to Vice President Dick Cheney, and was involved in representation of people involved in the case of a suspicious death of a woman held in a CCA facility. In addition to compiling information about Puryear for the Senate Judiciary Committee tasked with approving the appointment, Friedmann also organized other organizations, including Alliance for Justice, Grassroots Leadership, and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, among others, to oppose his nomination. On January 2, 2009, the nomination was returned to the White House, effectively denying Puryear the appointment."[11]

"Risk Factors" in SEC Filings

Below is a list of some of the more notable "risk factors" CCA lists in its 2012 Form 10-K Annual Report:[1]

- "We are subject to fluctuations in occupancy levels, and a decrease in occupancy levels could cause a decrease in revenues and profitability" (p. 26)

- "The operation of correctional and detention facilities by private entities has not achieved complete acceptance by either governments or the public" (p. 27)

- "The movement toward privatization of correctional and detention facilities has also encountered resistance from certain groups, such as labor unions and others that believe that correctional and detention facilities should only be operated by governmental agencies" (p. 27)

- "The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices or through the decriminalization of certain activities that are currently proscribed by criminal laws" (p. 27)

- "For instance, any changes with respect to drugs and controlled substances or illegal immigration could affect the number of persons arrested, convicted, and sentenced, thereby potentially reducing demand for correctional facilities to house them. . . . Our policy prohibits us from engaging in lobbying or advocacy efforts that would influence enforcement efforts, parole standards, criminal laws, and sentencing policies" (p. 28)

- "The return of the California inmates to the state of California would have a significant adverse impact on our financial position, results of operations, and cash flows" (p. 31)

History

CCA is the oldest and largest private prison corporation in the U.S. It was founded (with help from venture capitalist Jack Massey) in January 1983 by Tom Beasley, then-head of the Tennessee Republican Party; Doctor Robert Crants, a Nashville lawyer and businessman; and (Terrell) Don Hutto, former Arkansas prison director, and at the time of CCA's founding, Virginia state corrections director and president of the American Correctional Association (ACA).[132][133]

CCA Founder T. Don Hutto's Leadership of Arkansas Prisons Leads to Landmark Supreme Court Decisions on "Cruel and Unusual Punishment"

In the 1970s, during Hutto's tenure as prison director in Arkansas, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the entire Arkansas penal system constituted cruel and unusual punishment.[134]

In his majority opinion in Hutto v. Finney, Justice Stevens summarized the conditions as such: "The administrators of Arkansas' prison system evidently tried to operate their prisons at a profit. See Talley v. Stephens, supra, at 688. Cummins Farm, the institution at the center of this litigation, required its 1,000 inmates to work in the fields 10 hours a day, six days a week, using mule-drawn tools and tending crops by hand. 247 F. Supp., at 688. The inmates were sometimes required to run to and from the fields, with a guard in an automobile or on horseback driving them on. Holt v. Hutto, 363 F. Supp. 194, 213 (ED Ark. 1973) (Holt III). They worked in all sorts of weather, so long as the temperature was above freezing, sometimes in unsuitably light clothing or without shoes. Holt II, 309 F. Supp., at 370."[134]

The Court had earlier taken supervisory jurisdiction over the Arkansas penal system and issued remedial orders, but found that those orders were not followed: "in some respects, conditions had seriously deteriorated since 1973, when the court had withdrawn its supervisory jurisdiction."[134] Hutto was appointed prison system commissioner in 1971.[135]

See also: "Prisons: Hell in Arkansas," Time Magazine, February 9, 1968.

Sodexo's Investment in CCA (1994-2000)

In 1994, Sodexo, a multi-national French corporation and the world's largest private contractor for food services, acquired between 8 and 17 percent of Corrections Corporation of America in stock.[136] By 2000, Sodexho Alliance (now called Sodexo Group) was the largest investor in the company. In March 2000, however, the Prison Moratorium Project organized universities across the country to expose Sodexo's connection to CCA. In the campaign, Not With Our Money, students pressured schools to cut contracts with Sodexho Marriott (now Sodexo Inc.), the university food service subsidiary of Sodexho Alliance, if they did not divest from the CCA's operations. After losing contracts with six universities, Sodexo announced in 2001 that it would sell all investments in CCA.

However, this move did not mean Sodexo was out of the private prison business. In 2000, before Sodexo had disinvested from CCA, CCA sold Sodexo a 50 percent share of UK Detention Services. Sodexo already owned the other half of the company, meaning that Sodexo gained sole ownership of that UK prison company.[137]

Personnel

CEO

Damon T. Hininger is CCA's President and Chief Executive Officer. He joined the company in 1992 as a correctional officer at Leavenworth Detention Center in Leavenworth, Kansas and quickly moved up through the ranks of the company.[138] In 2013, his total annual compensation, including base salary, stock options, and other compensation, was over $3.2 million.[139] In 2011, Hininger was named one of the "20 Most Powerful CEOs Age 40 or Under" by Forbes Magazine.[140]According to SEC filings, from 2009-2013 Damon T. Hininger reportedly made a total of $11,469,167. [141][139]

- 2009 : $1,733,547

- 2010 : $3,266,387

- 2011 : $3,696,798

- 2012 : $2,772,435

- 2013 : $3,282,460

- Total : $14,751,627

According to SEC filings, the top five CCA executives, including Hininger, made $29,656,315 from 2008-2013. [141][139]

- 2008 : $1,376,625

- 2009 : $3,876,737

- 2010 : $7,713,043

- 2011 : $8,772,031

- 2012 : $7,917,879

- 2013 : $9,315,698

- Total : $38,972,013

Executive Leadership

As of August 2013, other executives include:[138][142]

- Tony L. Grande, Executive Vice President and Chief Development Officer - total compensation in 2013: $1,554,861

- Harley G. Lappin, Executive Vice President and Chief Corrections Officer - total compensation in 2013: $1,514,706. Harley Lapin was formerly a director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), which gave CCA a $129 million dollar contract for incarcerating immigrants in a Mississippi facility during Lapin's tenure.[133]

- Todd J. Mullenger, Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer - total compensation in 2013: $1,675,986

- Steve E. Groom, Executive Vice President & General Counsel - total compensation in 2013: $1,287,685

For more information on executive compensation, see CCA's Schedule 14A Proxy Statement.

Board of Directors

As of August 2014:[131]

- John D. Ferguson, Chairman of the Board, Former Commissioner of Finance and Administration for the State of Tennessee

- Donna M. Alvarado, Former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, U.S. Department of Defense

- John D. Correnti, Member of Audit Committee, CEO of SteelCorr, Inc.

- Dennis DeConcini, former U.S. Senator from Arizona

- Robert J. Dennis, President and CEO of Genesco, a specialty retailer of footwear, headwear, and sports apparel

- Mark A. Emkes, former Commissioner of Finance and Administration for the State of Tennessee, former Chairman and CEO of Bridgestone Americas Holdings, Inc.

- Damon Hininger, President and Chief Executive Officer

- C. Michael Jacobi, Former President and Chief Executive Officer of Timex Corporation

- Anne L. Mariucci

- Thurgood Marshall, Jr., son of the historic Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, former Cabinet Secretary to President Clinton

- Charles L. Overby, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of the Freedom Forum

- John R. Prann, Jr., Former President and CEO of Katy Industries, Inc.

- Joseph V. Russell, President and CFO of Elan-Polo, Inc.

Contact Information

Corrections Corporation of America

10 Burton Hills Boulevard

Nashville, TN 37215

Phone: (615) 263-3000; (800) 624-2931

Fax: (615) 263-3140

Web: http://www.correctionscorp.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/correctionscorp

Twitter: https://twitter.com/CorrectionsCorp

Resources and Articles

Key Reports

- In the Public Interest, [Bed Guarantees Report], organizational report, September 19, 2013.

- Grassroots Leadership, The Dirty Thirty: Nothing to Celebrate About 30 Years of Corrections Corporation of America, organizational report, June 2013.

- Suevon Lee, By the Numbers: The U.S.’s Growing For-Profit Detention Industry, ProPublica, June 20, 2012.

- Caroline Isaacs, Private Prisons: The Public's Problem A Quality Assessment of Arizona's Private Prisons, The American Friends Service Committee, February 2012.</ref>

- Corazón de Tucson, The Corrections Corporation of America: How CCA Abuses Prisoners, Manipulates The Public and Destroys Communities, organizational report, January 2012.

- Cody Mason, Too Good to be True Private Prisons in America, The Sentencing Project, Report, January 2012.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2011, December 2012.